Artistry is at the heart of numerous creations, from stunning paintings to captivating graphic designs, all of which can find protection under copyright and design law. Take, for instance, a decorative fabric design; it’s eligible for copyright protection or can be registered under the Design Act, showcasing its artistic merit. This grey area is a common pitfall for fashion items, which often blur the line between fast fashion and true works of art.

Just consider the mesmerising Medusa dress by Schiaparelli; it’s hard to see it as anything less than an artistic masterpiece. Or think about Victor & Rolf’s gravity-defying upside-down fashion, where models strutted down the runway in clothes styled diagonally, horizontally, and even upside down. These striking designs transcend traditional fashion; they embody the very essence of art itself. Fashion undeniably belongs in the realm of art, but not all of it. The innovative techniques and creativity that go into crafting fashion items are nothing short of breathtaking. With each piece, designers push the boundaries of imagination, making it clear that fashion is a true form of artistic expression deserving of our admiration.

Image: Viktor & Rolf Spring Couture 2023

Source

BACKGROUND

Fashion has always danced on the delicate line between inspiration and imitation, and the ongoing struggle to protect designs has brought some high-profile cases to the forefront. One striking example is the case of Ritika Private Limited vs. Biba Apparels Private Ltd.( CS(OS) No.182/2011), where renowned designer Ritu Kumar found herself unable to defend her unique creations after BIBA replicated them. The catch? Ritu had not registered her designs under the Design Act of 2000, leaving her vulnerable in a competitive industry.

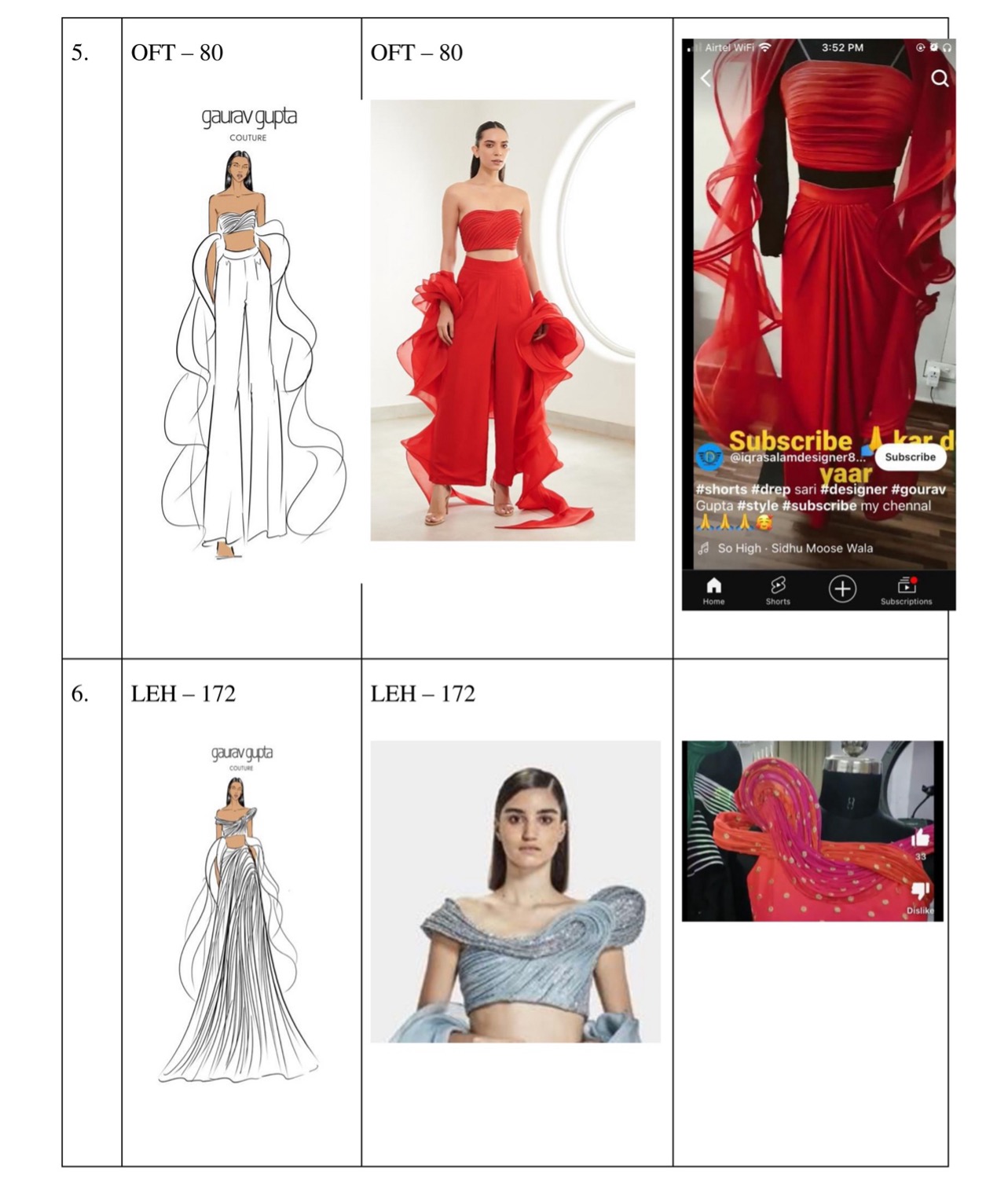

Now Fast fast-forwarding to a more recent showdown, wherein a celebrated Indian designer known for dressing various celebrities, Gaurav Gupta, has taken a stand against alleged copyright infringement (M/S Reflect Sculpt Private Ltd. & Anr v. Abdus Salam Khan (CS(COMM) 278/2024)). The Delhi High Court heard the case where Gaurav was claiming that his signature ‘sculpted boning’ technique was unlawfully mimicked by the respondents. In a twist of fate, the court sided with Gupta, noting that the handmade nature of his work and the sale of less than 50 copies meant the protections under Section 15(2) of the Copyright Act didn’t apply. Additionally, the court highlighted that Sections 14(1)(c) and 51 of the Copyright Act shield his innovative designs from being replicated in other forms. These cases not only shine a light on the complexities of design protection but also underscore the importance of safeguarding creativity in the fashion world.

To understand this, one must understand the conundrum of section 15(2) of the Copyright Act. Section 15(2) of the Copyright Act of 1957 addresses the overlap between copyright and design protection. It guarantees that copyright does not last forever for industrial designs that can be registered under the Designs Act of 2000, but have not been registered. It simply means:

- If a design is capable of being registered under the Designs Act (i.e., it has visual appeal and can be applied to an article by an industrial process),

- And it is not registered,

- Then, copyright protection ends after 50 reproductions of the design.

Image: M/S Reflect Sculpt Private Ltd. & Anr v. Abdus Salam Khan.

TEST TO RESOLVE THE DILEMMA

In a recent and significant ruling, the Supreme Court tackled a pressing conflict in the case of Cryogas Equipment Private Limited v. Inox India Limited & Ors (2025 LiveLaw (SC) 426). The court introduced an intriguing twin test to address these kinds of disputes, shedding light on how to navigate such challenging situations. This decision promises to have important implications for future cases.

Inox India Limited claimed that LNG Express India and Appellant-Cryogas Equipment had violated its copyright in engineering drawings and books about cryogenic semi-trailers used to transport LNG. The appellants asserted that the drawings were unregistered ‘designs’ under the Designs Act, 2000, and hence, ineligible for copyright protection under Section 15(2) of the Copyright Act following industrial usage, while Inox maintained that the drawings were original ‘artistic works’ under the Copyright Act.

The question at hand revolves around an intriguing dilemma: when does a piece of artistic work lose its copyright protection because it’s being used on an industrial scale? This shift raises the fascinating possibility that it might be redefined as a ‘design’ under the Designs Act. It’s a captivating intersection of creativity and legality that sparks essential conversations about ownership and innovation. The Bench stated:

“(i) Whether the work in question is purely an ‘artistic work’ entitled to protection under the Copyright Act, or whether it is a ‘design’ derived from such original artistic work and subjected to an industrial process based upon the language in Section 15(2) of the Copyright Act;

(ii) If such a work does not qualify for copyright protection, then the test of ‘functional utility’ will have to be applied so as to determine its dominant purpose.”

The Court made an important observation: the fact that a work is used solely for commercial purposes doesn’t automatically strip it of its copyright protection. However, what’s important to consider is its functional utility. As the Court stated, if the main feature of a work is its utility or practical use rather than its artistic charm, it won’t meet the criteria for protection under the Designs Act. In order to emphasise the absence of a unified worldwide strategy, the verdict used international treaties like as TRIPS and the Berne Convention in addition to comparative law from the United States, including the US Supreme Court’s decision in Star Athletica LLC v. Varsity Brands Inc. Therefore, question of Copyright and Design overlap is a matter of National policy.

This decision revealed that the parliament aimed to have stronger safeguards for works of pure artistic expression, like paintings and sculptures, while offering only limited protection for designs driven by commercial interests. Hence, it is important to classify fashion also into these two categories.

CONCLUSION

In the world of fashion, distinguishing between artistic expression and commercial intent can be quite a challenge. At its core, the answer is straightforward: runway designs that showcase originality and artistic flair can be safeguarded as works of art through copyright protection. On the flip side, fast fashion, driven entirely by commercial motives, won’t find refuge under the Copyright Act in India. Instead, it must look to the Design Act of 2000 for the protection it seeks. Fashion is not just about creativity; it’s also about knowing where and how to defend that creativity!

References:

- https://www.livelaw.in/supreme-court/supreme-court-lays-down-twin-test-to-resolve-copyrightdesign-conflict-under-s152-of-copyright-act 289433?fromIpLogin=68967.24709069477

- https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2024/10/16/from-art-to-industry-decoding-the-clash-between-copyright-and-design-in-indian-law/

- https://www.mondaq.com/india/copyright/1223274/overlap-between-copyrights-and-designs-in-india

- https://spicyip.com/2025/04/part-i-cryogas-judgment-supreme-court-stops-copyright-from-gaslighting-design.html

- https://www.bananaip.com/intellepedia/copyright-vs-design-protection-supreme-court-ruling-cryogas-inox/

- https://www.mondaq.com/india/copyright/1493464/indian-fashion-industry-intersection-of-copyright-and-design-law

- https://aarnalaw.com/insights/copyright-in-fashion-safeguarding-designers-creative-works