The luxury resale market involves buying and selling pre-owned high-end goods, such as certain designer bags, watches, and apparel, as well as collectables like jewellery, magnets, and magazines, which are valued at a very high price due to their vintage appeal. We are witnessing a significant boom in the market that has accelerated in recent years. It used to be a niche market of consignment shops and vintage boutiques, but now it has grown into a global industry valued in the tens of billions of dollars.

Thanks to social media, which also in a very colossal way contributes to showcasing what a luxury lifestyle should look like and does look like, it contributes to creating a sense of wanting to access through the exclusivity chains, and this gives a huge nudge to the consumer base of today and the youth of today to actually go for the luxury resale products.

This surge is driven by cost consciousness, and we can even say that it is specific to eco-minded consumers, especially Gen Z and Millennials, who see second-hand luxury as a way to obtain coveted items more affordably, which is sustainable. At the same time, the trend has raised important questions about sustainability, intellectual property rights, and privacy.

Luxury brands have a tense relationship with resale brands. Some partners with resale platforms or in-house programs to adopt the circular economy and market themselves in a greener way, avoiding specific legal challenges that can arise, while others fight legal battles to protect their brand image and exclusivity to the best of their ability.

In this in-depth exploration, we will examine exactly how luxury resale has evolved from a niche subject to a mainstream phenomenon, what its environmental impacts are, the legal and IP issues it raises, the role of technology such as RFID tags and digital authenticity certificates, and what both entrepreneurs and consumers should keep in mind in this fast-growing sector.

Tracing the Evolution of the Luxury Resale Market

Previously, buying second-hand was stigmatised in the luxury world, which thrives on exclusivity and the first-hand experience of acquiring luxury. With that perspective, traditionally affluent shoppers preferred new and exclusive items and brands, seeing that they were banking on such aspects, tightly controlling their products and distribution. Historically, the resale market for luxury goods remained very limited, restricted to local vintage shops, pawnbrokers, and, later, online auction sites such as eBay in the early 2000s.

However, we have witnessed a change over the past decade. Dedicated luxury resale platforms have professionalised this industry. Companies such as The RealReal, based in the US, Vestiaire Collective, based in Europe, Fashionphile, Rebag, and Chrono24, which specialises in watches, authenticate and curate pre-owned luxury items, providing buyers with the confidence that when they buy, they are purchasing quality and authenticity.

The second-hand luxury market, which grew 28% in 2022, is valued at about $45 billion globally, far outpacing growth in primary luxury retail. In fact, one study found that the luxury resale segment grew five times faster than the first-hand luxury market between 2017 and 2021, primarily driven by the convenience that online platforms offered.

Customer demographics have also played a massive role in this boom. Demand has surged from the earlier perspective of stigma to now, with young shoppers opting for the trend and loving vintage. Demand for vintage designer bags has increased by 300% since 2020, and Gen Z consumers spent 40% more on second-hand luxury bags in 2023 than they had previously. Many see buying pre-owned items as a savvy way to access brands like Chanel, Hermès, or Rolex without paying the full retail price or going through long-drawn processes. This purchase is often viewed as a smart investment. For instance, tracking the increase in the value of limited-edition handbags, such as the Hermès Birkin and the Chanel Classic Flap Bag, as well as iconic Swiss watches, has shown their potential to appreciate over time due to scarcity and collectable appeal.

Growing at a healthy clip as collectors and newcomers trade timepieces, the luxury resale boom has prompted established brands to respond. Some have begun to incorporate resale into their business models, embracing the trend, while others resist – a dichotomy that warrants attention.

We Are Following the Lens of Sustainability and Circular Fashion: How Green Really Is the Resale Market?

One of the most prominent claims about the resale trend is that it promotes sustainability through its circular fashion model. By extending the life cycle of luxury goods through refurbishment, resale keeps the products in circulation longer and out of landfills, where they may or may not decompose, theoretically reducing the demand for newly manufactured items. This is the simple, derived, and understood base of cycle extension, unlike fast fashion, which is often produced cheaply and disposed of even more quickly.

High-end luxury items are typically made to last because of the quality materials and craftsmanship that go into them, as per how the brand markets itself, which makes them well-suited for reuse by multiple owners over decades. In this sense, luxury resale aligns with waste reduction and resource conservation goals.

For instance, a very recent industry report found that if premium and luxury apparel brands implement robust resale programs, they are likely to see a 15% to 16% reduction in their annual carbon emissions by 2040, alongside a roughly 30% decrease in their need for new production each year. This could be maintained while keeping commercial interests viable, allowing them to fulfil their commitments toward the sustainability chain of command they promise whenever a brand makes a green claim.

There are luxury brands that have matched onto this narrative. When launching their own resale initiatives, companies often tout the environmental benefits to better position themselves in terms of green labour. For instance, Hugo Boss claims that on average, a second-hand purchase has 44% lower carbon emissions than buying new items. That makes sense because there was no new production or manufacturing process. Lululemon has described its resale platform as a significant step toward a circular ecosystem. This fits right into the shoes that Europe has been trying to make all these brands wear when it comes to circularity and stopping ultra-fast and fast fashion. RealReal even developed a sustainability calculator for its customers, showing that greenhouse gas and water usage are saved by consigning or purchasing certain items instead of buying them new.

Of course, a flip side and a cautionary tale exist here. Experts caution that resale is not a silver bullet for the fashion sustainability problem. The context matters the most.

From the Legal Lens: The Trademark Battle, Authenticity, and the Right to Resell

Generally, IP law in many jurisdictions recognises a first sale or exhaustion doctrine, which means that after the first authorised sale of a product, the original IP owner’s rights to control further distribution of that specific item are exhausted. It is this very principle that these resale brands are now using to protect themselves.

However, the first sale doctrine comes with caveats. Crucially, it only applies if the item was indeed put on the market with the brand’s authorisation in the first place. Since it is going back into the market, and the market is another substantial factor that must be looked at, a secondary commercial exploitation is now being conducted. If goods are obtained through unauthorised channels, for instance, factory overruns, stolen merchandise, or items marked “not for resale”, the brands can argue that those items were never legitimately sold, thus blocking their sale as trademark infringement.

This issue arose in Chanel’s lawsuit against reseller What Goes Around Comes Around, where Chanel identified certain boutique display items, like showcase décor never meant for sale, and even some allegedly stolen factory goods that WGACA had sold. The court agreed that because Chanel never authorised the sale of those particular items in the first place, the first sale doctrine could not protect WGACA from those sales.

Even in cases when items are genuine, trademark law continues to apply in how resellers market and present those luxury goods. So, while a reseller can use the brand’s name to identify the product they are selling truthfully, this is known as nominative use of a trademark; they cannot create the impression that they are affiliated with or authorised by the brand if they are not.

Chanel has sued both WGACA and The RealReal, alleging that these platforms’ heavy use of Chanel’s trademarks and marketing language mislead consumers into thinking that Chanel somehow approves resale companies or that Chanel has authenticated the products.

One landmark comparison is Tiffany & Co. v. eBay (2008). In that case, the luxury jeweller Tiffany sued eBay for facilitating the sale of counterfeit Tiffany items by third-party sellers. The U.S. court ruled that eBay was not liable for trademark infringement because the counterfeit items were sold on its platform, since eBay did not sell the goods itself and did not have specific knowledge of each infringement. Notably, the court also stressed that eBay never claimed to authenticate the goods, as it was a neutral marketplace.

However, the situation with modern resale platforms differs since they are not in the same territory as counterfeit. Companies like The RealReal and WGACA actively authenticate and curate inventory, inserting themselves into the transactions as professionals verifying the product. Chanel’s argument in suing these platforms is partly that if they market themselves as authenticators, they bear responsibility for any fakes that slip through. They must be cautious not to give a false impression of the brand’s value.

It’s also worth noting that laws can vary globally. In the European Union, for example, trademark exhaustion is “regional” rather than international – a luxury brand can often prevent unauthorized imports of its genuine products from outside the EU (parallel imports), even if those products are authentic.

From the Lens of Technology, Authentication, and Privacy in Resale

Because trust serves as the real currency in the resale market, to sell to buyers who must stay confident that they are getting the real deal, brands and resellers alike are investing in high-tech solutions from microchips to blockchains to make it a point that a Louis Vuitton bag or a Patek Philippe watch being resold is the same genuine item that left the factory. These measures can dramatically reduce the counterfeiting problem that also troubles the IP sector and the luxury market, and they give buyers more confidence and raise specific questions. Could the embedded chips and digital IDs pose privacy issues for the owner? How much information should a product have about its history and new owners?

A widely adopted tool is RFID, which stands for Radio Frequency Identification tagging, and its close cousin, NFC, or Near Field Communication. These are tiny chips or tags that can be embedded in a product, sewn into a handbag’s lining, hidden in a watch, or attached to a clothing label, which broadcast a unique identifier when scanned by an appropriate reader. Luxury brands have begun inserting these chips to act as a kind of wireless fingerprint. For example, the LVMH Group launched the Aura blockchain in 2019, a platform where each product gets a unique cryptographic token on an RFID or NFC chip, allowing a consumer or reseller to scan the item and instantly verify its authenticity via a tamper-proof digital certificate. This token can now record the product’s life cycle, from raw materials to manufacturing to the point of sale, and then beyond to resale.

The same applies to watchmakers like Vacheron Constantin, part of Richemont, which issues digital certificates for premium watches in its Les Collectionneurs program, ensuring that each timepiece comes with a traceable blockchain-backed authority. There are also independent tech companies, such as Arianee, which provide a universal platform for digital passports related to luxury goods. An Arianee digital identity is essentially an NFT (non-fungible token) that identifies each product and can be transferred to identify the new owner when resold.

The benefits of these technologies are clear: they make it much harder for counterfeiters to fool consumers, but they come with the responsibility to maintain built trust and facilitate smoother resale transactions. They can also help in cases of theft. However, specific concerns come with these advances, mainly privacy considerations.

An RFID tag, by design, broadcasts a signal (albeit a very short-range one). The concern is that unauthorised scanners could read the tag. For instance, imagine a chip in your luxury handbag: in theory, a tech-savvy individual with an RFID reader could scan your bag as you walk by and retrieve its identifier. If that identifier is linked to a database, they might learn what type of bag it is, or even who originally bought it. These are documented worries that RFID tags might be used to track or profile consumers without consent.

Additionally, some tags are deactivated at purchase or made removable by the consumer if they wish to opt out after authentication. The key is that brands must be transparent about these technologies. Consumers should know if the product they buy has a tracking chip and what it does.

Another privacy angle worth looking into is digital certificates and how recent platforms use them. When you authenticate or register a product, even if you do so voluntarily, through the brand’s system, you may be required to provide personal data, such as your name, contact details, and purchase information. If the brand or platform requires you to create an account to transfer a digital certificate to your name, that data could be used for marketing or other purposes. Data leaks can happen even if not used for marketing, as has occurred in cases involving several luxury brands such as Cartier. Second-hand buyers might inadvertently expose themselves to a brand’s data ecosystem, which they were unaware of when the item was first sold. While nothing inherently nefarious about a brand wanting to know its customers, even second-hand customers, it raises the question of data privacy and consent.

As regulations like the European Union’s GDPR require, consumers should have control and knowledge over how their data is used. In practice, a balance can be achieved. Systems like Arianee claim to let owners verify authenticity anonymously. You hold a cryptographic proof of ownership without handing over personal identifiers.

Conclusion and Key Takeaways

The luxury resale market is no longer optional; it is becoming an integral part of how luxury is experienced. Both businesses and consumers need to adapt to these changes.

For Businesses and Entrepreneurs:

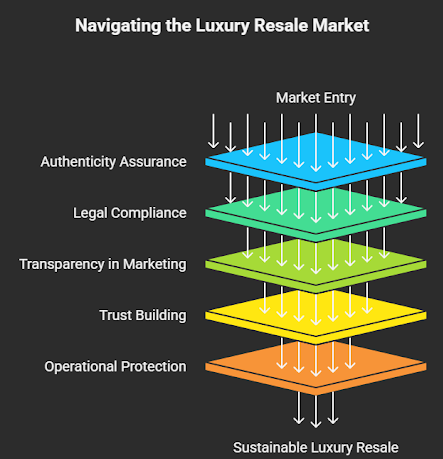

- Authenticity is the foundation. Skilled authenticators, RFID/NFC tools, and zero tolerance for counterfeits are non-negotiable.

- Stay legally safe. Operate within trademark first sale rights, use brand names only descriptively, and always add disclaimers of independence.

- Be transparent in marketing. What you show must match what you sell and remain within legal boundaries.

- Build trust with both sides. Treat consignors fairly and give buyers guarantees, clear policies, and professional presentation.

- Remain agile. Track shifts in demand (today Gucci, tomorrow Fendi) and adjust quickly.

- Protect operations. Have strong contracts, insurance, and data privacy safeguards in place. Tech adoption must respect consumers’ rights over their data.

For Consumers:

- Do your homework. Research platforms, verify authenticity, and check items carefully on arrival.

- Know the market. Some items come with resale premiums. Be aware before buying.

- Pay securely. Stick to safe payment methods, and you will avoid off-platform deals.

- Keep evidence. Document purchases: when, from whom, and under what terms.

- Choose sustainability. Buy second-hand instead of new, but be mindful of shipping footprints.

The bottom line is that luxury resale balances access, profit, and sustainability if both sides act responsibly.