When we talk about icons in music, the great voices that have left their mark throughout their careers automatically come to our mind and Madonna is no exception, in fact, she is the queen of pop to this day.

As a singer, she undoubtedly has favorable reviews of her works from music journals such as Pitchfork or Rolling Stones. Her most famous and iconic works were compiled in Celebration (2009) where songs like ‘Like a Virgin, Hung Up or Isla Bonita’ stood out. But there is a song in particular in which there is a relationship between fashion, performance and music: Vogue.

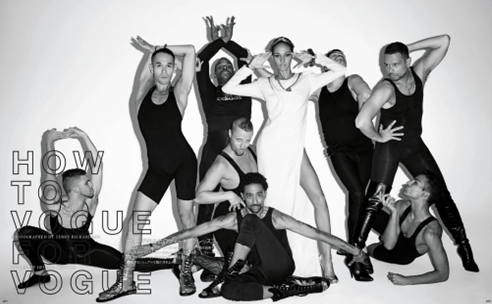

The song was published in 1990, both Madonna and the composer Shep Pettibone were inspired by the movie Paris is burning and when the singer went to a club in Manhattan for the first time where they practiced vogue. Vogue or voguing is an artistic expression created by the black and Latino queer communities in the suburbs of New York between 1960-1980 as part of the ballroom culture as a form of resistance towards racial, sexual and gender inequalities. Now, if we look for the relationship between the artistic movement and Vogue magazine, they are very connected to each other. The dance steps were inspired by the movements of Egyptian hieroglyphics as well as Vogue magazine models in terms of modeling aesthetics.

That is to say, the culture of vogue or voguing was inspired by the elegance and empowerment that the angular movements of the Vogue models transmitted on their catwalks. The perfect symbolized opulence and status, a contrary and distant reality that some queer member of the neighborhood could experience. For this reason, in a way, dance also served as a parody of this due to the strong contrasts of a reality (from a magazine) versus a reality contextualized in the suburbs, as mentioned in a quote from the movie Paris is Burning: “For us, dance it is the closest we will get to the reality of fame, fortune, stardom and spotlights” (1990)

Now, it’s not just the poses that have to be rewarded to Vogue, but also fashion as such. The diversity of the LGBTIQ+ community is expressed through what is considered drag. Drag queens wear exaggerated makeup and dress in a satire of themselves or what is considered “girly” and incorporate fashion and pop culture influences into their clothing. For example, Rupaul’s Drag Race commonly sees tributes to great Vogue models like Naomi Campbell. Although the model is not part of the community, she has been a source of inspiration by being one of the first successful racialized models on the fashion catwalks in addition to her great avant-garde in the industry as well as being an advocate for the rights of the community.

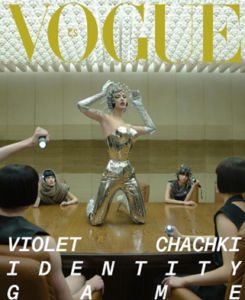

Although within the first years there was no direct recognition by magazines such as Vogue towards drag queens, over the years the magazine has made the community visible by presenting drag queens such as Plastique Tiara, Sasha Velor or Violet Chachki in the magazine as well as inviting them to the MET Gala on behalf of Vogue (as in the case of Violet Chachki). Little by little, Vogue is beginning to position them as main covers in their magazines considering the impact of drag culture in recent years and the level of popularity they have reached as well as influencing multiple sectors in art such as cinema, fashion, music, among others.

And in music, today, we can observe Vogue’s interest in allowing its space as a platform for the dissemination of music by queer artists in various musical styles such as hyper pop, considering that the differences between a heterosexual artist and a queer one difference is overwhelming due to gender bias. However, Vogue has made it possible to spread the life, career and styles of artists like Kim Petras by giving her a voice to express herself as well as to promote her.

Bibliography:

Dörner, A. (1994). [Review of The Madonna Connection. Representational Politics, Subcultural Identities, and Cultural Theory, by C. Schwichtenberg]. Politische Vierteljahresschrift, 35(1), 172–173. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24196892

Harper, P. B. (1994). “The Subversive Edge”: Paris Is Burning, Social Critique, and the Limits of Subjective Agency. Diacritics, 24(2/3), 90–103. https://doi.org/10.2307/465166

Author: Adela Jesus Canchasto Acho