The Working of the Global Fashion Trade and the Rise of Ultra-Fast Retailers

When we talk about massive, dynamic, and constantly abuzz global enterprises, fashion would naturally be among the top leaders, with revenue statistics projected to reach US$920.19bn in 2025. Amidst all that goes on in the background, whether it is trade tensions, geopolitical shifts, or the trends shaped by them, you must have come across those bait posts that claim that if a particular trend is coming back, it is a recession indicator. I cannot say how much truth there is to that, but I take away from such posts that the conversation around fashion and luxury markets is incomplete without understanding trade and international sentiment.

Production and consumption have surged multifold in the past two decades, driven by the advent and acceptance of fast fashion through digital commerce and globalised supply chains. This growth has also meant a monumental increase in the number of people engaged in these supply chains, catering to the demands of agile, data-driven production networks. The business model and philosophy of ultra-fast fashion take this up several notches.

Pioneered by companies that come first to mind, like Shein and Temu, ultra-fast fashion accelerates the design-to-sale cycle dramatically, introducing thousands of new styles and micro-trends every day and selling them at ultra-low prices. Charting a different route from the traditional retailers, who generally ship bulk inventory to stores or regional warehouses, ultra-fast fashion players increasingly ship direct-to-consumer overseas. This allows them to capitalise on the efficiency of international postal and courier networks. While the direct e-commerce model helps them cut many costs of physical retail, it has also revealed serious gaps in how such technology was meant to adapt in trade and taxation, exposing weaknesses in global tax and customs frameworks.

This article presents the multiple layers that make fast fashion business models strikingly resilient through their adept strategies of exploiting tax loopholes in the global trade system, and explains why such gaps must be examined to ensure these business models pay their share of costs at specific terminals for the damage they cause.

Tax Loopholes in Low-Cost Fashion Imports

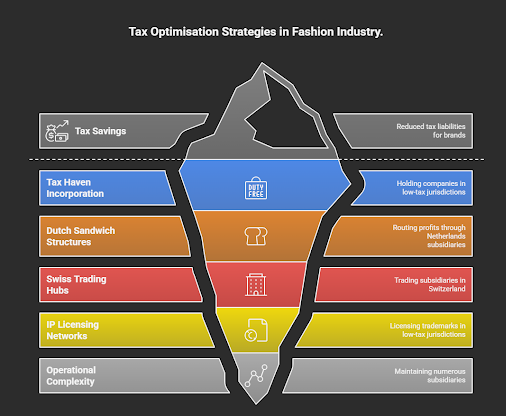

Penned down decades ago from the perspective of servicing ease and seamless operational support in furtherance of administrative convenience, international trade rules and tax policies continue to follow certain thresholds and exemptions. However, these prove inept in today’s e-commerce-driven fashion trade, where such provisions have significantly evolved into major tax loopholes. For instance, ultra-fast fashion retailers routinely manipulate the de minimis customs value threshold, VAT (value added tax) exemptions on low-value goods, and related low-value consignment relief schemes to minimise or entirely avoid import duties and taxes on inexpensive apparel. These practices are enabled by virtually impenetrable and sophisticated architectures of corporate layering and linked tax optimisation strategies, which allow businesses to systematically exploit the gaps while externalising massive environmental and social costs.

The primary layer begins with the discussion on tax haven incorporation. Several multinational fashion brands actively seek to establish, or have already established, their ultimate holding companies in tax havens such as Ireland, which offers around 12.5 per cent corporate tax, as well as the Netherlands and Switzerland. This creates the shock-absorbing and foundational layer for tax optimisation.

The next layer then consists of the intermediate operational layers. In the intermediate operational layers, what can be observed is that sophisticated fast fashion companies employ multiple layers that serve distinct optimisation functions. The first to discuss would be the Dutch sandwich structures. Certain companies channel their profits through Netherlands-based subsidiaries, collecting royalty-style payments from retail operations and paying only 15% tax on billion-dollar revenues. This single mechanism has saved them millions during specific periods.

Next are the Swiss trading hubs. Some companies establish their base trading subsidiaries in Switzerland, purchasing low-cost goods from suppliers at artificially low prices and then reselling them to Spanish parent companies with substantial profit margins, benefiting from the Swiss corporate tax rate as low as 7.8%. This mechanism again results in savings of hundreds of millions of dollars and euros over the long term.

Third are the IP licensing networks. Fast fashion brands license their trademarks and brand rights to subsidiaries located in low-tax jurisdictions. This allows them to collect royalty payments taxed at preferential rates rather than standard corporate tax rates in high-tax manufacturing or retail countries. It simultaneously creates and protects exclusivity through IP asset registration and licensing while ensuring that tax positions remain protected.

Finally comes the operational complexity layer. Several fast-fashion parent companies strive to establish and maintain more than 50 subsidiaries in strategic locations like the Netherlands or Switzerland, creating a web of interconnected entities that make it extremely difficult for tax authorities to trace profit flows and assign appropriate tax liability. This very complexity serves both as a tax optimisation tool and a regulatory arbitrage mechanism.

Furthermore, there are specific rules that ultra-fast fashion retailers manipulate to minimise or, in some cases, entirely avoid import duties and taxes on inexpensive apparel. The first to discuss in greater detail would be the de minimis customs threshold. Many countries have already set a de minimis value under which imported goods incur no import duty, and sometimes even no tax, to avoid the cost of processing trivial customs payments. The United States has one of the world’s highest thresholds at $800. Any shipment valued at $800 or less can enter the U.S. tariff-free with minimal customs formalities. This rule stands codified under Section 321 of the U.S. Tariff Act. Initially intended for gifts and small personal imports, ultra-fast fashion companies are now exploiting it on an industrial scale. Cheap items like $10 dresses routinely land in U.S. mailboxes duty-free, moving across the country outside the scope of import taxation.

It is natural to understand that when import duties are reduced, there is a greater incentive and a wider margin for profit maximisation for ultra-fast fashion players. In practice, this means more goods being shipped, often in smaller packages, taking advantage of the threshold. In 2015, Congress raised the U.S. de minimis cap from $200 to $800 just as the wave of e-commerce shipments was about to explode, making the U.S. threshold an outlier globally. Similarly, in Mexico and Canada, thresholds are relatively high due to trade agreements. Canada allows duty-free imports up to C$150, and Mexico will enable imports up to $170. By contrast, India’s de minimis threshold is effectively zero rupees. All imports are subject to duties and taxes from the first rupee of value, reflecting a more stringent regime, particularly when viewed from the perspective of discouraging fast and ultra-fast fashion.

The second tool exploited is the VAT exemption and low-value consignment relief, or LVCR. In many jurisdictions with value-added tax, low-value imports historically enjoyed VAT relief. For a long time, the European Union exempted imports under €10–22 from VAT, and the UK exempted goods under £15. These rules were introduced in the 1980s to reduce customs paperwork on negligible-value parcels. However, this relief soon created distortions. Companies established fulfilment hubs just outside the EU, notably in the UK’s Channel Islands, to mail products like CDs, cosmetics, or fashion items to EU customers VAT-free. By 2012, the UK, acting upon the pervasive exploitation of the VAT-free structure, moved to end the LVCR regime after noticing abuse via the Channel Islands, extending VAT to all imports from that territory regardless of value. The EU followed suit on 1 July 2021, scrapping its €22 VAT-free threshold. Now, any business-to-consumer import will be subjected to VAT. After such a shift, the EU established that it would require VAT payment, often handled through new systems like the Import One-Stop Shop.

Even with these reforms in place, specific challenges remain. Fraudulent undervaluation of parcels to reduce VAT or slip under the EU’s €150 customs duty threshold is reportedly widespread. EU officials have estimated that up to 65% of e-commerce parcels were undervalued to stay below €150 and avoid customs duties, prompting proposals to remove that €150 duty exemption in the coming years.

The third set of tools or strategies used are undervaluation, parcel splitting, and gift schemes. Viewing beyond the already formally in place thresholds, fashion importers exploit tactics from the book of creative logistics and declarations, to exploit the glaring loopholes.

One tactic is parcel splitting, dividing a larger order into multiple small packages, each keeping it under the de minimis limit. Another is undervaluing goods on invoices: for example, a $30 item might be declared as $10 to slip under the tax threshold or attract a lower duty rate. Several e-commerce sellers were also on the move to abuse provisions meant for gifts. Till 2019, India allowed gifts up to ₹5,000 to enter duty-free. Several Chinese e-tailers like Shein, Club Factory, and AliExpress, previously allowed to conduct their business in India, massively exploited this by marking commercial orders under the header of gifts under ₹5,000. In response to the exploitation of the clause, India banned duty-free gifts entirely in 2019, with only limited exceptions still in place, such as life-saving medicines and the festival of Rakhi. Likewise, many companies have tried declaring goods as sample shipments or using false descriptions to avoid import taxes and scrutiny. Such manoeuvres take advantage of the gaps between the letter of customs rules and the reality of e-commerce trade.

Trade Agreements, Tax Treaties, and the Unintended Consequences

Fast fashion’s resilience comes from its masterful exploitation of existing global tax and trading systems gaps through sophisticated corporate layering, transfer price manipulation, and regulatory arbitrage. Tax and trade policies cannot now be viewed in isolation. Various international agreements and treaties have inadvertently contributed to the current landscape in which many low-cost fashion imports thrive.

For instance, free trade agreements have sometimes pushed countries to raise their de minimis limits. The United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) explicitly required Canada and Mexico to increase their duty-free thresholds for express shipments. While this is understood to be essential for other industries, fast fashion companies exploit it to maximise profit. Under USMCA, Canada went from a C$20 threshold, which was long criticised by consumers as very low, to a C$150 threshold for duty-free entry, with GST exempt up to C$40. While this can be seen as a trade facilitation measure, it must also be examined through the lens of accountability for fast fashion.

International Customs and Postal Agreements play an equal role here. Under the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement and the Universal Postal Union (UPU), there is a push for smoother processing of small parcels and faster clearance. The WTO does not directly set de minimis values but encourages risk-based customs control, which often means low-value packages are given a green channel.

While these treaty issues relate more to corporate profit taxes than import taxes, they form part of the structural incentives that make ultra-fast fashion financially viable across borders without assuming responsibility for the waste and damage created.

Conclusion and Takeaways

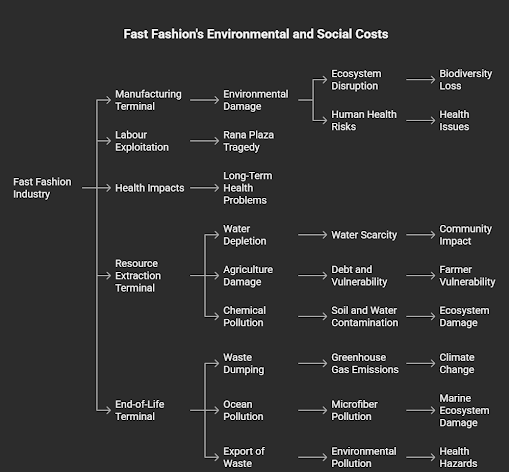

The resilience guaranteed by such structures comes at the cost of externalising massive environmental and social damage across critical terminals of the value chain, from the cotton fields to the factory floors to the landfills in developing countries where these products and parcels ultimately end up.

- Manufacturing terminal costs: Environmental damage is immense. Textile dyeing alone accounts for 20% of global wastewater pollution, with toxic chemicals permanently contaminating rivers, groundwater, and soil fertility, affecting ecosystems and the health of nearby communities.

- Labour exploitation: 75 million factory workers worldwide are engaged in this industry, with fewer than 2% earning a decent wage. 80% are women, many facing harassment and unsafe conditions. The Rana Plaza tragedy stands as a permanent reminder of this exploitation.

- Health impacts: Owing to the unsafe working conditions, employed workers are regularly exposed to toxic chemicals without adequate protection or safety training, leading to long-term health problems that companies fail to not only compensate for, but also inform about them as their legal right to claim, despite legal obligations.

- Resource extraction terminal costs: Fast fashion’s consumption of natural resources is severe.

- Water depletion: The industry consumes 93 billion cubic meters of water annually, with 10,000 litres required per kilogram of cotton.

- Agriculture damage: Pesticide contamination, chemical dispersion into water, and land displacement worsen conditions for farmers, often perpetuating cycles of debt and vulnerability.

- Chemical pollution: Toxic substances from fibre production contaminate soil and water resources. Even when garments end up in landfills, these pollutants continue to leach into the environment. Natural fibres and synthetic fibres each present distinct but equally damaging challenges.

- End-of-life terminal costs: The disposal phase represents an enormous externalisation of costs to future generations and developing countries.

- Waste dumping: 85% of textiles end up in landfills once trends fade. Ultra-fast fashion’s algorithm-driven micro-trends have produced 92 million tons of textile waste annually.

- Ocean pollution: 500,000 tons of microfibers from synthetic clothing enter the oceans yearly, equivalent to 50 billion plastic bottles.

- Export of waste: Used clothing is shipped to developing countries, where much remains as waste. This shifts the disposal burden onto countries that did not benefit from the original production and are ill-equipped to handle the costs.

Together, these impacts show an imperative cost and urgent need for closing tax gaps. Indeed, in the beginning, the industry and individual companies would witness revenue losses or market distortions in the short term, but addressing these loopholes contributes to the larger necessity of accountability in fashion. The costs externalised onto people, environments, and future generations far outweigh the profits captured through loophole-enabled resilience.