Case Background

The case involves diamond engagement rings sold at Costco using the trademarked term TIFFANY. In November 2012, a customer alerted Tiffany to rings at Costco advertised as Tiffany’s,[i] prompting Tiffany to request removal of the mark from Costco’s display case signs.[ii] Costco also offered refunds for unsatisfied customers.[iii]

In February 2013, Tiffany filed a complaint against Costco for trademark infringement, counterfeiting and other violations under the Lanham Act and New York law.[iv] Costco responded by denying infringement and seeking a judgment to declare Tiffany’s mark invalid.[v] Costco also made counterclaims, including: (1) the TIFFANY mark was used just to describe the products, not as a trademark; and (2) the TIFFANY mark has become generic for a multi-prong, solitaire ring setting.[vi]

Tiffany replied, clarifying that its original complaint was about Costco’s use of the TIFFANY mark, not the term “Tiffany Setting,” emphasizing Costco’s signage used TIFFANY without mentioning “Tiffany Setting.” [vii] Eventually, both parties filed cross-motions for summary judgment.[viii]

In September 2015, the district court ruled for Tiffany, granting summary judgment and awarding $21 million in damages.[ix] Costco subsequently appealed the decision. The Second Circuit Court of Appeals determined that factual questions should have gone to a jury, not decided by the court.[x] It agreed with Costco that there were genuine issues of material fact regarding the trademark infringement and counterfeiting.[xi] Additionally, it held that Costco was entitled to present its fair use defense to a jury.[xii] As a result, the Second Circuit overturned Tiffany’s $21 million judgment, vacated the summary judgment in favor of Tiffany, and remanded the case for trial.[xiii]

District Court Sides with Tiffany

Filing a motion for summary judgment seeks a decision from the district court without the need for a full trial. At the summary judgment stage, the judge’s role is not to determine the truth or weigh the evidence, but to assess whether there is a genuine issue for trial.[xiv] If a jury could reasonably reach a different conclusion based on the evidence, a jury trial is necessary, and the judge cannot decide on that issue at the summary judgment stage.[xv]

Here, Tiffany filed for summary judgment seeking three outcomes: (1) a ruling on Costco’s liability for trademark infringement and counterfeiting, (2) the dismissal of Costco’s fair use affirmative defense, and (3) the dismissal of Costco’s counterclaim that the TIFFANY mark had become generic.

- Costco Infringed Tiffany’s Mark

To win an infringement claim under the Lanham Act, the plaintiff must show (1) that it owns a mark that is legally protected, and (2) that the defendant’s use of the mark is likely to confuse consumers.[xvi]

With respect to the first prong of the test, Costco argued that the term “Tiffany” has become generic in the context of a specific style of pronged ring setting.[xvii] However, because Costco did not provide admissible evidence to challenge the validity and ownership of Tiffany’s marks, the court concluded that Tiffany made a prima facie showing of the mark’s validity, thus satisfying the first prong of the infringement test.[xviii]

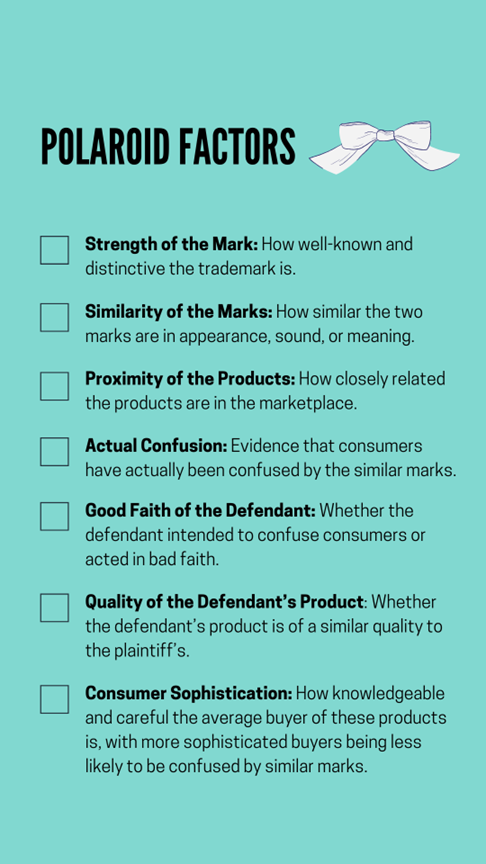

With respect to the second prong of the test, the court concluded that Costco failed to offer any evidence raising a disputed issue of material fact regarding any of the following Polaroid factors.

- Actual Confusion: Costco tried to discredit Tiffany’s evidence of customer testimonies and an expert survey by questioning the expert’s credentials and the methodology of his surve[i] However, Costco did not present any strong counter-evidence or its own survey proving that consumers were not confused by its use of the TIFFANY mark.[ii] Costco’s expert also failed to show Tiffany’s survey was inadmissible.[iii] To the court, Costco’s criticism of Tiffany’s evidence goes to the weight, rather than the admissibility, of Tiffany’s consumer confusion evidence.[iv] As a result, the court found that Tiffany’s evidence of consumer confusion was strong and unrebutted by Costco.[v]

- Good Faith: Tiffany provided evidence of an email from a Costco employee wanting their jewelry boxes to look more like Tiffany’s and a deposition where Costco’s jewelry buyer admitted to customer confusion.[vi] Costco argued that it used TIFFANY generically to describe a pronged diamond setting, providing dictionary entries, a publication excerpt, an affidavit from a diamond buyer, and a declaration from an Assistant General Merchandise Manager.[vii] Moreover, Costco asserted that it extracted the word TIFFANY from vendor-supplied information where it is used in a purely descriptive sense.[viii] However, the court concluded that no reasonable person could find that Costco acted in good faith in adopting the TIFFANY mark.[ix]

- Consumer Sophistication: Tiffany’s evidence relied on its expert’s survey of potential Costco diamond ring buyers.[x] Costco argued that diamond ring buyers are highly discerning and that Tiffany’s survey didn’t target the consumers with a present interest in buying a diamond ring.[xi] However, because Costco’s evidence only went to the weight that Tiffany’s evidence should be accorded, and Costco failed to provide its own evidence to counter Tiffany’s claims, the court found no genuine issue of material fact regarding consumer sophistication.[xii]

Applying these Polaroid factors, the court ruled in Tiffany’s favor, granting Tiffany’s motion for summary judgment regarding Costco’s liability for trademark infringement.[xiii]

- Costco Counterfeited Tiffany’s Mark

To win a counterfeiting claim under the Lanham Act, the plaintiff must prove that the defendant’s mark is “spurious” and closely resembles a registered mark, and that its use is likely to cause confusion, to cause mistake, or to deceive consumers.[xiv]

Tiffany supported its counterfeiting claim with emails, photos, and deposition testimony showing Costco’s use of the Tiffany mark to imply authenticity.[xv] Tiffany also highlighted that Costco placed the Tiffany mark prominently on display case signs, where typically the manufacturer’s name would appear for other products.[xvi] Costco argued its use of TIFFANY was not deceptive, citing an expert who stated that its rings had non-Tiffany marks, packaging, and paperwork.[xvii]

The court was not convinced, highlighting that Tiffany had shown actual consumer confusion, that Costco used a mark identical to Tiffany’s, and that Costco acted in bad faith.[xviii] The lack of the Tiffany mark on the rings themselves was not dispositive. In addition, Costco did not prove that using generic marks reduced confusion.[xix]

Therefore, the court concluded that Costco has not raised any material issues of fact regarding these findings and granted Tiffany’s motion for summary judgment on Costco’s counterfeiting liability.[xx]

- Costco’s Fair Use Defense is Rejected

Fair use defense requires demonstrating that the use of the mark was not as a trademark, was descriptive, and was done in good faith.[xxi] If a defendant successfully proves these elements, they may argue that their use of the mark should be protected under the fair use doctrine, even if it causes some consumer confusion.

Since the court has already determined that Costco did not act in good faith when adopting the Tiffany mark, Costco failed to satisfy a crucial element of the fair use defense.[xxii] Therefore, Tiffany was entitled to summary judgment, striking down Costco’s fair use defense.[xxiii]

- Tiffany’s Mark is Not Generic but a Source-Identifier

A generic mark is a term that has become commonly used to describe a type of product or service, rather than to identify the source of that product or service. Generic terms are not protectable because they do not distinguish one source of goods or services from another. Hence, when a defendant asserts genericism in a trademark infringement case, they are essentially arguing that the term be invalidated as a federal trademark.[xxiv] In Tiffany’s case, it would allow any retailer to use the term TIFFANY in connection with rings.[xxv] In other words, this would mean the invalidation of a 184-year-old trademark and all the goodwill that has come to be associated with the brand.[xxvi]

Based on Tiffany’s expert report, 90% of potential jewelry buyers saw TIFFANY as a brand name when viewed alone, and 30% saw it as a brand name or both a brand name and descriptive term when seen in Costco’s context.[xxvii] Based on this, Tiffany argued that TIFFANY is seen by the public as a brand name and accordingly its mark cannot be considered generic.[xxviii] Costco countered with its own expert report criticizing Tiffany’s study methodology and suggesting that the term could be both a brand name and a descriptive term for a ring setting.[xxix]

The court was not convinced by Costco’s arguments. Costco’s criticism of Tiffany’s evidence pertained to the weight it should be accorded by the jury, rather than its admissibility.[xxx] Moreover, Costco provided no legal authority for the term TIFFANY to be both a registered mark and a generic word.[xxxi] The court acknowledged the Second Circuit’s “dual usage” doctrine, which allows a mark to start as a proprietary word and later become generic to some segments of the public.[xxxii] However, Costco did not address this doctrine or provide any factual evidence to support its dual usage, and the court chose not to explore this argument on its own.[xxxiii]

Moreover, the court pointed out that Costco did not present any evidence creating a material fact issue about whether the primary significance of the TIFFANY mark was as a “generic descriptor” or a “brand identifier.”[xxxiv] The court emphasized that determining the primary significance of the mark is essential for deciding if it is generic.[xxxv]

Therefore, the court ruled in favor of Tiffany, finding that Costco did not raise a material fact issue regarding the generic nature of the TIFFANY mark, and granted summary judgment against Costco’s genericism counterclaim.[xxxvi]

Second Circuit Appellate Court Sides with Costco

On appeal, Costco mainly challenged the district court’s evaluation of three factors: actual customer confusion, whether Costco acted in bad faith by using Tiffany’s mark, and whether the consumers were sophisticated enough to avoid confusion.[xxxvii] The appellate court determined that Costco had presented a triable issue on each of these points, which extended to the broader question of whether Costco’s actions likely caused customer confusion.[xxxviii]

- Genuine Dispute of Trademark Infringement Exists

a. Actual Confusion

The appellate court held that Tiffany did not conclusively prove customer confusion. Limited instances of confusion—only six out of over 3,349 purchases—might be seen as minimal by a reasonable juror.[xxxix] Costco further bolstered its case with expert testimony challenging Tiffany’s survey, arguing it was flawed because Tiffany surveyed consumers without a present interest in buying a diamond ring and used contrived and biased stimuli that did not reflect real-life point-of-sale conditions.[xl] Unlike the district court, the appellate court found that the weight given to Tiffany’s survey could determine whether Tiffany was entitled to summary judgment or if a jury could find a material fact favorable to Costco.[xli]

b. Good Faith

The appellate court found that Tiffany had not conclusively established bad faith on Costco’s part. While Costco aimed to emulate “useful, nonprotected attributes” of Tiffany’s products, this intent did not necessarily imply an intention to deceive customers about the jewelry’s origin.[xlii] The court noted that subjective matters like good faith are not suitable for summary judgment, suggesting that a jury could reasonably interpret Costco’s actions as inspired by Tiffany’s designs rather than intended to mislead.[xliii] Furthermore, Costco provided evidence that it extracted the word TIFFANY from vendor descriptions[xliv] and used TIFFANY as a generic style term to denote a type of pronged setting.[xlv] Costco also took steps to differentiate its products from those of Tiffany, such as using different branding and packaging.[xlvi] Hence, a jury could reasonably interpret Costco’s use of the term as not malicious but aimed at accurately describing the jewelry style to customers.[xlvii]

c. Consumer Sophistication

The appellate court disagreed with the district court’s assertion that Costco failed to prove its customers were sophisticated enough to avoid confusion, viewing this as shifting the burden of proof onto Costco.[xlviii] Again, the appellate court reiterated that the weight of a piece of evidence can be determinative as to whether summary judgment is appropriate.[xlix] Costco’s expert even presented evidence that actual buyers are knowledgeable and discerning, likely recognizing that Tiffany did not produce Costco’s rings.[l] Therefore, a jury could reasonably conclude that the relevant consumers would understand this distinction.[li]

d. Overall Likelihood of Consumer Confusion

The appellate court determined that Costco’s evidence collectively raised a genuine question about the likelihood of customer confusion.[lii] This conclusion was primarily based on two factors: Costco demonstrated that “Tiffany” is widely understood to describe a specific style of pronged ring setting, and it showed that consumers of diamond engagement rings are generally knowledgeable and discerning.[liii] A reasonable jury could therefore conclude that consumers would recognize Costco’s use of TIFFANY solely in a descriptive sense, not as an indication of origin.[liv] While Costco’s use of TIFFANY may have created a potential for confusion, given Costco’s evidence and Tiffany’s failure to show otherwise, the court declined to rule definitively that no reasonable jury could find Costco’s signs non-confusing.[lv]

- Costco is Entitled to the Fair Use Defense

The appellate court held that Costco is entitled to present its fair use affirmative defense at trial.[lvi] At the trial court level, there was sufficient evidence to support all three elements of Costco’s affirmative defense.[lvii] However, having resolved the motion on the basis of good faith alone, the district court did not consider the other factors pertinent to the fair use defense.[lviii]

a. First Element Satisfied: Use of the Mark Not as a Mark

The appellate court found that a jury could reasonably conclude that Costco did not use the term TIFFANY as a trademark.[lix] Tiffany’s evidence showed that Costco typically places the trademark at the beginning of product labels, but none of the hundreds of engagement ring signs produced for this litigation began with TIFFANY.[lx] Instead, the term TIFFANY was displayed similarly to setting information for other rings.[lxi] Costco also provided evidence that the word TIFFANY did not appear on any of its rings or packaging, which instead bore the logo of a different manufacturer.[lxii]

b. Second Element Satisfied: Descriptive Use of the Mark

The appellate court found that a jury could reasonably conclude that Costco used the term TIFFANY descriptively.[lxiii] Costco provided evidence showing that TIFFANY is widely understood to refer to a specific type of pronged diamond setting, separate from the Tiffany brand.[lxiv] Costco identified over a century’s worth of documents and included declarations from employees and vendors supporting this descriptive use.[lxv] Furthermore, Costco demonstrated that it used the term exclusively on signs for rings with a Tiffany setting, displaying consistent information across all engagement ring styles.[lxvi] This evidence supported the argument that TIFFANY has a descriptive meaning in the jewelry trade and that Costco’s use was in good faith: “There is nothing inherently absurd about a single word’s being both a source identifier and a descriptive term within the same product class.”[lxvii] For the appellate court, Tiffany’s lack of challenge to the terms “Tiffany set” or “Tiffany setting” may suggest an implicit recognition of some descriptive uses of its mark.[lxviii]

- Tiffany’s Trademark Counterfeiting Claim is Dismissed

Since the appellate court deemed it inappropriate to hold Costco liable for trademark infringement at the summary judgment stage, and considering that counterfeiting is considered an aggravated form of infringement, it also vacated the district court’s judgment on the counterfeiting claim as well

Implications for the Fashion Industry

In July 2021, Tiffany and Costco have settled their long-running lawsuit.[lxix] However, its significant and lasting consequences persist for the fashion industry.

- Genericization of “Tiffany”: Similar to terms like Escalator and Aspirin that have become generic, if TIFFANY becomes widely used to describe a specific type of pronged diamond ring setting, it may lose its trademark protection.[lxx] This could allow various retailers like Costco to use the term TIFFANY to describe such settings without facing infringement claims.[lxxi]

- Dual Usage Doctrine: This case underscores the concept that a term can serve both as a trademark and have a legitimate descriptive function within the same industry. This dual usage may lead to more disputes over the protectability of descriptive terms.[lxxii]

- Descriptive Fair Use Defense: Using a term descriptively rather than as a trademark may serve as a defense against counterfeiting claims.[lxxiii]

- Good Faith Imitation: As the case demonstrated, imitation of unprotected product features does not automatically indicate bad faith.[lxxiv] This distinction is crucial for litigants to discern between protected and unprotected elements in trademark infringement cases.[lxxv]

- Weight of the Evidence Matters: The Second Circuit’s emphasis on reviewing Polaroid factors anew could lead to stricter scrutiny in granting summary judgments.[lxxvi] This is because the weight of a given piece of evidence can be determinative of whether summary judgment is appropriate. District courts may thus exercise greater caution in granting summary judgment, particularly when the weight of evidence is contested rather than new evidence being presented.[lxxvii] This is of concern for companies with even the most aggressive of intellectual property practices.[lxxviii] Also, if a brand that serves a dual descriptive purpose within its industry sees its mark’s value diminish, the company could have less incentive to expend substantial costs associated with maintaining federal trade registrations and enforcing its intellectual property rights.[lxxix]

Author Bio: Seoryung Park

Seoryung Park is a New York licensed attorney with a certificate in IP. She earned her J.D. from the University of Connecticut School of Law, where she served as an associate editor for the Connecticut Journal of International Law. She holds a B.A. in criminology, sociology, and political science from the University of Toronto.

With a background in teaching, Seoryung has a passion for educating others about fashion law. She aims to write articles that merge international perspectives, cultural insights, and thorough explanations, making complex legal matters accessible and engaging for every reader.

[i] Id. at 12-13.

[ii] Id. at 13-14.

[iii] Id.

[iv] Id. at 14.

[v] Id.

[vi] Id. at 15.

[vii] Id. at 15-16.

[viii] Id. at 16.

[ix] Id.

[x] Id. at 19-20.

[xi] Id. at 19.

[xii] Id. at 19-20.

[xiii] Id. at 20.

[xiv] Id.

[xv] Id. at 21.

[xvi] Id.

[xvii] Id. at 21-22.

[xviii] Id. at 22.

[xix] Id.

[xx] Id. at 23.

[xxi] Id.

[xxii] Id. at 24.

[xxiii] Id.

[xxiv] Keene, supra note 9.

[xxv] Id.

[xxvi] Id.

[xxvii] Tiffany, No. 13CV1041-LTS-DCF, at 25.

[xxviii] Id.

[xxix] Id. at 25-26.

[xxx] Id. at 28.

[xxxi] Id. at 27.

[xxxii] Id.

[xxxiii] Id.

[xxxiv] Id. at 30.

[xxxv] Id.

[xxxvi] Id.

[xxxvii] Tiffany, 2020 WL 4556537, at 18.

[xxxviii] Id. at 18.

[xxxix] Id. at 21.

[xl] Id. at 20-21.

[xli] Id. at 21-22.

[xlii] Id. at 23-25.

[xliii] Id.

[xliv] Id. at 24.

[xlv] Id. at 27.

[xlvi] Id.

[xlvii] Id.

[xlviii] Id. at 29-30.

[xlix] Id. at 29.

[l] Id. at 29-30.

[li] Id.

[lii] Id. at 30.

[liii] Id.

[liv] Id. at 31.

[lv] Id. at 32.

[lvi] Id.

[lvii] Id. at 33-34.

[lviii] Id. at 33.

[lix] Id. at 34.

[lx] Id.

[lxi] Id.

[lxii] Id. at 35.

[lxiii] Id. at 36.

[lxiv] Id.

[lxv] Id.

[lxvi] Id.

[lxvii] Id. at 37.

[lxviii] Id. at 39.

[lxix] Keene, supra note 9.

[lxx] Edward Weisz & Keren Goldberger, The Price of Fame: Tiffany Settles 8-Year Lawsuit with Costco Over Use of Company Name in Ring Displays, TOTALRETAIL (last visited June 28, 2024), https://www.mytotalretail.com/article/the-price-of-fame-tiffany-settles-8-year-lawsuit-with-costco-over-use-of-company-name-in-ring-displays/.

[lxxi] Id.

[lxxii] McGuireWoods, Second Circuit Overturns Tiffany’s $21M Judgment Against Costco in Trademark Battle (Aug. 18, 2020), https://www.mcguirewoods.com/client-resources/alerts/2020/8/second-circuit-overturns-tiffany-21m-judgment-against-costco/.

[lxxiii] Id.

[lxxiv] Id.

[lxxv] Id.

[lxxvi] Id.

[lxxvii] Id.

[lxxviii] Kaitlyn Rodnick, Tiffany & Co. v. Costco Wholesale Corp.: Cut, Clarity, Carat, Color, and Costco?, Tul. J. Tech. & Intell. Prop. [Vol. 23], 232 (2021).

[lxxix] Id. at 233.

[i] Tiffany & Co. v. Costco Wholesale Corp., No. 13CV1041-LTS-DCF, at 3 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 8, 2015).

[ii] Tiffany, No. 13CV1041-LTS-DCF, at 4.

[iii] Id. at 4.

[iv] Tiffany & Co. v. Costco Wholesale Corp.*, Nos. 17-2798-cv, 19-338, 19-404, 2020 WL 4556537, at 8 (2d Cir. Aug. 17, 2020).

[v] McDonnell et al., Tiffany & Co. v. Costco Wholesale Corp.: TIFFANY Mark Infringed by Costco’s Sales of “Tiffany” Rings, JDSUPRA (Dec. 7, 2015), https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/tiffany-and-co-v-costco-wholesale-corp-86983/%3E.

[vi] Id.

[vii] Id.

[viii] Id.

[ix] Celes Keene, Tiffany & Co. and Costco Wholesale Settle Trademark Dispute, KLEMCHUCK (Aug. 3, 2021), https://www.klemchuk.com/ideate/tiffany-costco-trademark-dispute-settles.

[x] Tiffany, 2020 WL 4556537, at 2, 12.

[xi] Tiffany, 2020 WL 4556537, at 12.

[xii] Id.

[xiii] Id.

[xiv] Id. at 17.

[xv] Id.

[xvi] Tiffany, No. 13CV1041-LTS-DCF, at 6.

[xvii] Id. at 7.

[xviii] Id. at 6-7.