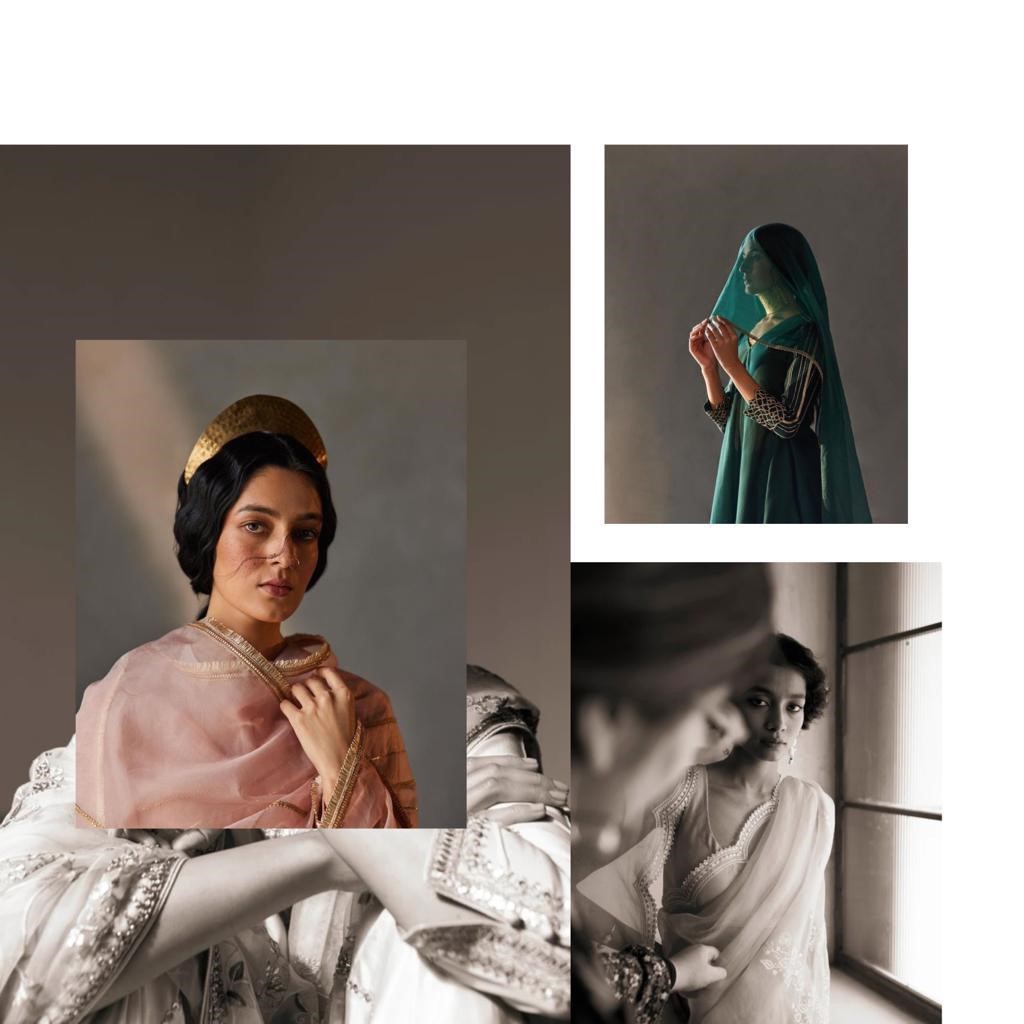

Design teams for high-end luxury brands like Gucci, Louboutin, and Prada produce highly desired products dictating fashion trends across the world. Fashion designers, especially in India are not only pillars of creativity and innovation but also contribute to a multi-billion dollar industry. Despite this, designers are unable to completely and totally protect their works the way a musician, for example, could. The manufacturing of clothing generates hundreds of billions of dollars annually. The 2021 sales forecast for the Indian fashion industry was $20 billion[1]. In 1999, the value of global clothing and apparel sales was estimated to be $784.5 billion[2]. The expansion of the fashion industry has increased public awareness of stylish “designer products.” This definitely calls for the protection and registration of apparel, jewellery and shoe design, because fashion may be a billion-dollar industry, but it still remains a vulnerable one.

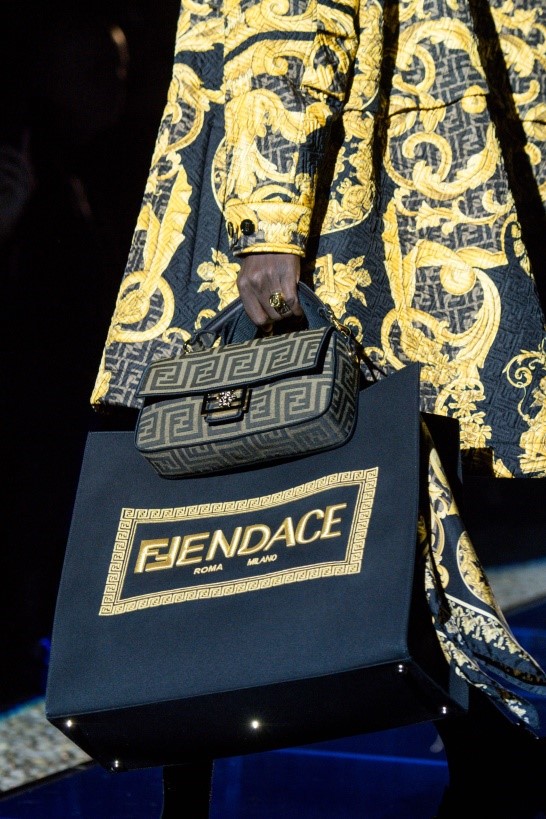

Although a fashion brand’s identity can be protected by trademark protection, it frequently loses its potency in the face of imitation or similar goods. When a first-copy/knockoff/ lookalike product copies the entire appearance of the original brand without using its name, and claiming Industrial Design Protection doesn’t seem feasible, copyrights offer an additional claim option when the original fashion design is a work of artistic craftsmanship. Industrial design protection safeguards the features that are unique to fashion labels and brands, such as decoration and design, and typically provides a quicker and more affordable way to register an IP. Industrial designs provide an additional means of enforcement by preserving the aesthetics of the entire product or a specific part of it.

Copyright is by far the most popular intellectual property right available in the world. Even so, it provides very little protection in the advent of fashion design. This is because clothing and other works of fashion do not neatly fit into any of the listed subcategories of “artistic works” (namely graphic works, photographs, sculptures or collages, works of architecture or works of artistic craftsmanship). The category that applies to the world of fashion the most is “work of artistic craftsmanship.” A work must be both artistic and a product of craftsmanship to fall under this heading.

Copyrights are just one example of how often design rights clash with other IP rights and unlike patents, design rights only provide protection for the aesthetic parts of the product rather than their technicalities. A registered design is copyrighted for ten years from the date of registration under Section 11 of the Designs Act. It is possible to extend the copyright protection for an additional five years. The registered owner of a design automatically acquires ownership of the design’s copyright. Because Section 15(1) of the Copyright Act forbids the application of copyright protection to a registered design, a design cannot be protected under both the Designs Act and the Copyright Act at the same time. The copyright in an unregistered design would also expire after it has been commercially reproduced by the owner or another person with his permission more than 50 times.

Such was the dilemma faced by the legal counsel of Ritika Apparels Ltd.[3], they struggled to establish the protection of their designs despite it being registered under the Copyright Act, 1957. The plaintiff’s employees consistently divulged the trade secrets apparently leading to an imitation of patterns by Biba. However, Biba contended that since the plaintiff had exceeded the production value by 50, they did not come under the ambit of copyright protection under section 15 (2) of the act. The Hon’ble court reaffirmed that in order for a design to be protected by copyright, it must be registered under the Designs Act; otherwise, once it has been produced more than 50 times using an industrial process, the design will no longer be covered by copyright.

A registered design is a statutory right and copyright is an inherent right. Copyright safeguards all creative works, whether they take the form of literature, the arts, music, or instructional materials. Examples of artistic work include drawings, photographs, jewellery, designs, and clothing. Design Rights include novel features of an article, be it two-dimensional or three-dimensional, features like its shape, composition of lines, colour palette, surface ornamentation, configuration, etc. all come under the protection of the Design Act, 2000. However, these features are more aesthetic than functional, and the aforementioned Act governs the submission, prosecution, and registration of industrial designs in India. The fact that copyright protection is offered as soon as an original article is created is a key distinction between the two types of IP. However, the Designs Act only offers protection for a product when the owner registers the design. The Act was passed to comply with international protection standards and provide designs with the minimal level of protection mandated by the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS).

The Delhi High Court’s decision in the case of Microfibres Inc vs. Girdhar& Co & Anr.[4] sought to make clear the differences between original artistic works that are protected under the Copyright Act and designs that can be registered under the Designs Act. A lawsuit for copyright infringement of the creative works included in the upholstery materials was brought by the Plaintiff, a manufacturer of upholstery materials, against the Defendants. However, the defendants argued that because they had produced the alleged artistic work more than 50 times and had the ability to register it as a design under the Designs Act, the plaintiff had no rights under either of the two Acts. The Division Bench while rejecting the Plaintiff’s claim of copyright infringement held “ … a famous painting will continue to enjoy the protection available to an artistic work under the Copyright Act. A design created from such a painting for the purpose of industrial application on an article so as to produce an article which has features of shape, or configuration or pattern or ornament or composition of lines or colours and which appeals to the eye would also be entitled design protection in terms of the provisions of the Designs Act. Therefore, if the design is registered under the Designs Act, the Design would lose its copyright protection under the Copyright Act but not the original painting. If it is a design registrable under the Designs Act but has not so been registered, the Design would continue to enjoy copyright protection under the Act so long as the threshold limit of its application on an article by an industrial process for more than 50 times is reached. But once that limit is crossed, it would lose its copyright protection under the Copyright Act. This interpretation, in our view, would harmonize the Copyright and the Designs Act in accordance with the legislative intent.”

The Bombay High Court determined in another decision[5] that an “article” is different from an “original artistic work.” The court reaffirmed that regardless of how it is reproduced, the original creative work is still protected by the Copyright Act. Nevertheless, it will be considered a design once it is applied using an industrial process to any good other than the artistic work itself in a two- or three-dimensional form, and if registered under the Designs Act, it will receive protection for a shorter period of time.

It is evident from a joint reading of the relevant provisions of the Designs Act and the Copyright Act, as stated in the Delhi High Court’s 2017 decision[6], that an article’s design for purposes of industrial production qualifies as a design for the purposes of the Designs Act and is registrable as such. The owner of a design, however, will lose ownership of the design once more than 50 of these articles have been produced if it has not been so registered. The court determined that the plaintiff in the current case had created the engineering drawings necessary to manufacture the ATL devices. Because they were designs, the ATL device drawings could be registered under the Designs Act. However, the Plaintiff also forfeited the copyright in the design pursuant to Section 15(2) of the Copyright Act because it failed to register the design and did not contest the fact that it had already produced more than 50 ATL devices through an industrial process.

Designers, creators and innovators work rather hard to come up with absolutely original works of art. Designers hardly ever register their fashion designs because the industry is always changing. The registered design and the general appearance of the item are protected for ten years. The Design Acts forbid anyone besides the owner of the product from making identical products or goods with designs that are similar to the registered design. If, after observing how the general public reacts to the design, the designer believes that the design will endure for years to come and be widely purchased, they should consider choosing design registration under the Designs Act. This will safeguard their inventiveness.

References:

[1] M. Soundariya Preetha, Apparel exports to cross USD 20 billion next fiscal, says Textiles Secretary (2022) <https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/Coimbatore/apparel-exports-to-cross-usd-20-billion-next-fiscal-says-textiles-secretary/article65076541.ece> accessed on 19 Dec 2022

[2] Safia A. Nurbhai, Style Piracy Revisited, 10 J.L. & POL’Y 489, 489 (2002)

[3] CS(OS) No. 182/2011

[4] 128 (2006) DLT 238

[5] AIR 2015 BOM 157

[6] Holland Company LP and Ors v SP Industries CS(COMM) 1419/2016