Paris wakes up on October 2025 to a scenario that is typically only found in movies. A group of robbers broke into the second floor early in the morning and took eight royal jewels that had once belonged to the House of Orléans, including sapphire pendants and diamond tiaras. Their value was believed to be around €88 million (Bennhold, 2025). These were shards of France’s cultural essence, not merely indulgences.

The heist, which took place in less than nine minutes, sparked both fascination and indignation. How could the most renowned museum in the world, an establishment created to preserve civilization’s treasures, be the site of such a bold loss? However, what it indicates about the law’s blind spot is what really shocks people, not the spectacle (Shamin, 2025). A structural weakness is revealed by the Louvre heist: legal protections for luxury frequently vanish into uncertainty when it combines with cultural heritage.

The shortcomings of current institutions for heritage protection, self-insurance, and restitution are exposed by the theft, and this paper explores how these gaps represent a larger ambiguity at the nexus of fashion, art, and national identity (Weaver, 2025). By doing this, it poses a seemingly straightforward query: how is “luxury” safeguarded as it fades into the past?

The Theft and Its Significance

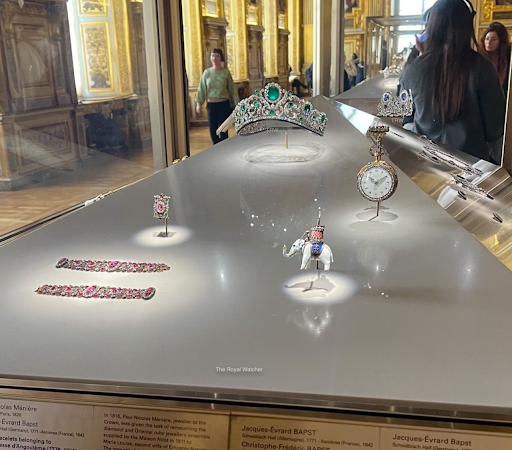

The Louvre issued a brief press release confirming the theft and claiming a “internal breach of security protocols (Shamin, 2025).” According to reports, the burglars targeted display cases containing French court jewels from the 19th century and used a digital override to get around alarm systems. The pilfered objects were on display from the French state’s history collection on a rotating basis. Notably, some of them were borrowed from the archives of Maison Chaumet, a partnership that honors “the artistry of French luxury.”

This crime’s symbolism was what caused it to have an international resonance. These diamonds, which had once adorned monarchs and had withstood wars, revolutions, and shifting fashions to become beautiful remnants of contemporary luxury, represented not only artistry but also heritage (Scott, 2025). Their loss is both artistic and financial because they were at the intersection of commercial status and cultural heritage.

Legal Vulnerabilities of Cultural Luxury

I. Heritage Protection and the Limits of the Law

In terms of cultural preservation, France is frequently seen as a world leader. The state’s obligation to safeguard “national treasures,” which are items of historical, cultural, or archaeological significance, is enshrined in the Code du patrimoine (Scott, 2025). However, when applied to items that fall in between art and decoration, this classification system becomes brittle, even though it is strong for paintings and monuments.

Jewels, couture items, and fashion archives are examples of luxury objects that rarely fall easily into heritage categories. Their dual status as commodities and cultural symbols makes their legal status more complex, even when they are on exhibit in public facilities. For instance, the cultural heritage law protects the Louvre’s collection of arts décoratifs, but it is unclear how to classify works that are borrowed from private maisons, such as Chaumet or Cartier. Are they considered commercial products or national treasures if they are stolen?

International frameworks are of limited assistance. Cultural artefacts are protected from cross-border trafficking by the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export, and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, but only if the originating country formally recognizes them as such (Shamin, 2025). This protection does not apply to many luxury goods, particularly those in private collections, which are never properly registered. Although it provides some protections, the European Union’s Regulation (EU) 2019/880 on cultural assets nonetheless gives fine art and archaeology precedence over applied arts.

Put differently, cultural luxury exists in a state of legal indeterminacy: too historical to be considered “mere merchandise,” too ornamental to be considered “heritage.”

II. The Paradox of Insurance

Like many large museums, the Louvre has a state-backed indemnity scheme for self-insurance. This approach shows faith in security protocols and an understanding that many pieces are, in reality, irreplaceable. However, self-insurance assumes the capacity to bear loss, a calculation that breaks down when the ownership and value of the item get muddled.

Chaumet’s heritage vault temporarily loaned many stolen pieces during the 2025 robbery. Despite being a part of LVMH, the maison is still a business, and its loan arrangements are based on private insurance plans that are different from state indemnity. This leads to a complex web of overlapping responsibilities: who is responsible for paying if private insurance does not cover damages brought on by governmental carelessness, and public indemnification covers the display but not the ownership?

This “moral hazard of glamour” highlights a more general reality. Spectacle is essential to cultural luxury because things need to be seen to maintain their aura, but being visible also makes one vulnerable. Their risk is increased by the very display of such items, which is necessary for their symbolic use. This paradox remains unresolved by current legal frameworks.

Furthermore, the valuation of traditional art insurance models is problematic. What is the cultural value of a royal diadem that was previously captured on camera by Richard Avedon or featured in Vogue archives? Nostalgia, status, and communal identity are difficult for the market to measure, yet the law demands a figure on paper

III. International Ownership and Restitution Issues

The recovery of the stolen jewels would rely on a patchwork of international tools if they resurfaced on the illicit market, possibly dismantled and sold through underground networks. The UNESCO Convention, INTERPOL alerts, and bilateral restitution agreements are all available to France, but the procedure is still difficult, particularly for goods whose provenance trails conflate private and public ownership.

Jewels don’t have provenance records or unique serial markings, unlike paintings. It is possible to melt settings and recut diamonds. Historical items whose stones predate contemporary tracking systems receive minimal help from the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme, which was created to reduce conflict diamonds.

This offers a philosophical and legal conundrum: who has the right to reclaim a cultural artefact that doubles as a luxury good—the country, the company, or the person whose heritage it symbolizes? Is recovering the stolen Chaumet tiara a question of criminal justice, intellectual property, or cultural diplomacy if it turns up at a Swiss auction? Every framework produces a different, incomplete response.

Thus, the heist at the Louvre highlights a gap that international law has not yet addressed between material property and cultural belonging.

Cultural Glamour’s Legal Vulnerability

Fundamentally, the Louvre robbery compels an examination of the concept of “cultural glamour.” These are items whose appeal stems from their embeddedness in popular culture as well as their uniqueness or craftsmanship. A diamond diadem transforms from a decorative piece to a performative symbol of civilization and a storehouse of memory.

However, glamour is not codified like heritage is. It doesn’t have any legal validity. The safeguards for fashion, such as copyright, design patents, and trademark legislation, focus on innovation in manufacturing rather than reverence for preservation. An item loses its living aura and is treated by the law as static heritage if it becomes a part of the national identity.

The legal brittleness of luxury’s cultural legacy is exposed by this disjunction. Jewellery or fashion enters a jurisdictional void when it transcends its market origin to become a historical emblem. The tangible—fabric, metal, stone—is protected by law, but not the ethereal glitz that gives them life. And it’s precisely that glitz that makes these items mythologized and so targets for theft.

In a way, the Louvre heist highlighted a paradox at the core of contemporary luxury rather than merely revealing a security flaw. We perceive it as myth, but we also ensure it as property and enshrine it as legacy. The legal system is unable to keep up with the cultural connotations that luxury currently conveys because it is still constrained by ownership and authenticity categories.

Conclusion: When Glamour Becomes Precarious

The theft of €88 million in royal jewels from the Louvre is more than an isolated crime; it is a parable of legal insufficiency. It reveals how the world’s most secure institutions depend on a patchwork of laws unfit for the hybrid realities of cultural luxury.

The legislation needs to change as fashion houses and museums work together more and more, as couture archives become part of public history, and as luxury becomes a language of identity. In order to acknowledge these hybrid objects as shared legacies rather than merely as possessions, future frameworks must incorporate intellectual property, cultural policy, and heritage law.

The empty display case in the Louvre serves as a metaphor for the time being, serving as a mirror that reflects the brittleness of the buildings designed to preserve beauty. Not only do gems disappear when luxury is looted, but the idea that beauty is secure once it is institutionalized also does.