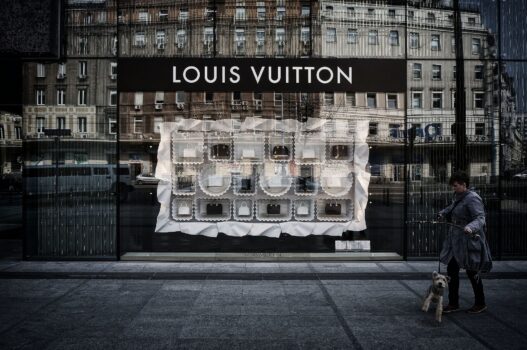

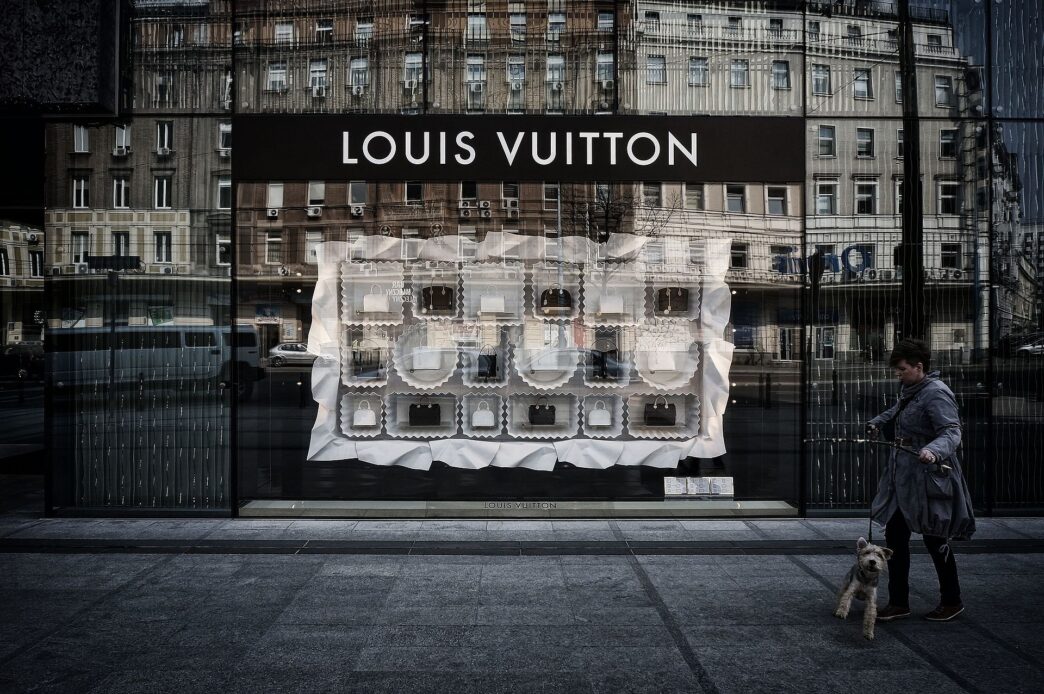

Louis Vuitton’s summer 2024 collection, By The Pool, unveils the French maison’s latest designs. Yet one piece has caused a huge stir among fashion enthusiasts and folk art lovers, who argue that the design is unmistakably inspired by Transylvanian traditional clothes. At the time of the collection’s debut, Louis Vuitton had neither acknowledged the source of inspiration nor addressed the clear resemblance to the traditional Romanian blouse. But to understand the full story, we must go back to the beginning…

Tracing the Threads: From Runway to Folk Roots

In 2012, Andrea Tanasescu founded the online community La Blouse Roumaine Ia Association, dedicated to showcasing the modernity of Romanian fashion and its deep cultural connection to its heritage. In early June 2024, members began reporting that Louis Vuitton had seemingly replicated the design and style of traditional clothing from the Oltenia and Muntenia regions of Transylvania.

A comparison posted on La Blouse Roumaine’s Facebook page revealed a striking resemblance between a piece in Louis Vuitton’s collection and a blouse from the Marginimea Sibiului region, an ethnographic area in southern Sibiu County.

Through a series of online posts, La Blouse Roumaine community called on Louis Vuitton to withdraw the products, emphasising that folk costumes are more than clothing, they are living witnesses to a culture’s history and should not be used without consent. Following these appeals, even the Romanian Ministry of Culture reached out to the fashion house, requesting formal acknowledgement of the heritage and cultural value of the garment. On June 25, 2024, La Blouse Roumaine announced via Instagram, that Louis Vuitton had recognised the issue, apologised, and withdrawn the pieces inspired by the traditional Romanian ia from its 2024 beach collection.

Although the matter never reached the courts, it provides an instructive opportunity to examine the legal dimensions of protecting folklore.

The Essence of Folklore

Because folklore is highly diverse, it is difficult to find a general definition acceptable to everyone. According to UNESCO’s recommendation, folklore (also known as traditional cultural expression) is the totality of the tradition-based creations of a cultural community. It can be expressed by individuals or groups, and it reflects the community’s cultural and social identity. Its patterns and values are mostly passed down and spread through oral tradition and imitation. Its genres, among others, include language, literature, music, dance, rituals, customs, handicrafts, architecture, arts, costumes, and clothing.

So here comes the big question: who owns the IP rights to folk costumes?

Folklore Protection at the Crossroads of Heritage and IP Law

In the case of folklore, protection can be approached in two ways. From a cultural heritage point of view, protection means identification, preservation, and protection from disappearance. In contrast, from an intellectual property perspective, protection means something else; it is about providing legal protection against unauthorized, abusive use that could exploit the right holders, the communities behind these traditions.

Interestingly, the UN Convention on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples combines both ideas. Article 11 declares the right of indigenous peoples to practice and revitalise their cultural traditions and customs. This includes, for example, the right to maintain, protect, develop, and express their designs and visual arts, not only from the past, but also in the present and the future. When it comes to intellectual property, Article 31 is particularly important. It states that traditional cultural expressions should be maintained, controlled, protected, and developed. However, there is one big limitation: this declaration is what we call soft law. In other words, it is more of a recommendation than a binding legal rule, therefore it has no actual legal force.

The issue of the protection of folklore under the Berne Convention has repeatedly appeared on the international agenda since the 1967 Stockholm revision, which included a provision (Article 15(4)) said to settle this issue. Since then, several developing countries, mainly in Africa, have provided in their statutory law for “copyright” protection on folklore. Yet, despite these efforts, it seems that copyright is not the right means for protecting expressions of folklore…

Folklore at the Edge of Copyright Law

Among the various mechanisms available under intellectual property law, copyright often appears to be the most suitable for protecting folklore. This article, therefore, turns to the question at the heart of the debate: can copyright protect traditional cultural expressions? To explore this, it requires an examination of both the advantages and the challenges. Let’s look at both sides.

Copyright is actually quite flexible. It can cover many different forms of creativity, just like folklore does. Unlike some legal tools, it does not always require works to be written down or fixed in a tangible form. That means even practices such as rituals, dances, or ceremonies could, in theory, be protected.

Another advantage is the set of moral rights it gives. For example, the publication of the work, the right to be designated as the author, or the right to integrity. Applied to folklore, this could help communities make sure their traditions are respected and not used in an offensive way.

However, there are also several difficulties in legal protection. The biggest drawback is the authorship. Copyright always needs a clear author, but folklore was created by communities over centuries. We simply do not know who the original “author” was, and when the work was created, so it does not fit into the individualistic system of copyrights. Even so, if a fashion designer creates an original garment that is inspired by traditional clothing or folk motifs, they may still be entitled to copyright protection.

Another problem is originality. Copyright protects works that have an individual and original nature. But many traditional expressions are ancient, shaped by generations, and do not meet this requirement anymore; therefore, they cannot be protected.

The limited duration of copyright protection can be a serious obstacle to its enforcement. Copyright protection usually lasts for 50 to 70 years from the first day of the year following the death of the author, the creation or the publication of the work. On the other hand, folklore is timeless, and it does not have an expiry date. When the term of protection expires, works fall into the public domain, and anyone can use them freely, which, in the case of folklore,e often leads to cultural globalization and the loss of diversity.

Finally, there is the problem of derivative works. If someone takes a traditional motif and turns it into something new, that new version can get copyright protection. This means that even someone from a completely different cultural background could obtain legal protection over something rooted in another community’s tradition.

Bringing Together the Threads: Balancing Law and Heritage

The question of protecting folk art often comes up whenever a fashion designer bases a collection on traditional costumes. But do we really need to give folklore legal protection? This topic divides even the experts.

One argument against it is that strict protection could limit creativity. If designers are not allowed to use folk motifs freely, they might not be able to give them a fresh, modern twist. At the same time, there is no doubt that global brands can help introduce the art of a region or ethnic group to the wider world. For example, Dolce & Gabbana presented a Mexico-inspired capsule collection, and Yves Saint Laurent’s iconic Africa collection is also worth mentioning here, where traditional culture inspired something new.

The problem is that often the people who enjoy protection over folklore have no connection to the communities that created it. One possible solution is what La Blouse Roumaine has long advocated: naming the source. That means the community of origin should be recognised, ensuring that their cultural interests are respected while still allowing designers to be inspired.

To sum up, folklore inspires, enriches, and connects us. But it also deserves respect, and maybe, the best way to protect it is not always through strict legal rules, but through recognition, transparency, and fairness.

Author: Dr. Kata Zsófia Prém

Dr. Kata Zsófia Prém is a PhD candidate at the University of Miskolc, Deák Ferenc Doctoral School of Law. Her research focuses on Intellectual Property Law, particularly copyright originality in fashion products. Her academic interests also encompass trademarks, designs, and various aspects of Fashion Law. She obtained her law degree in 2022. Fashion is her passion, and in her free time, she loves reading, baking, traveling, and spending quality time with her family and friends.