History will not only remember the treaties signed or the wars waged, but the wardrobes that framed them. Garments, long dismissed as frivolity, have always been statecraft in disguise — cloaks and crowns, uniforms and silks, each a jurisdiction of its own. In diplomacy, fabric is never mute; it speaks in the cadence of law.

The battlefield of modern conflict does not lie only in trenches or treaties. It lies, unexpectedly, in wardrobes. When the European Union barred Russian elites from acquiring couture in 2022, the embargo was not about dresses or handbags; it was about power and influence. In that instant, silk and leather became weapons, stitched into the arsenal of international law.

Fashion, often trivialised as ornament, revealed itself as an object of law — sanctioned, embargoed, and regulated with the gravity usually reserved for oil, steel, or arms. A Chanel gown withheld can sting as sharply as a frozen bank account; a Hermès bag denied at customs speaks the vocabulary of isolation louder than a diplomatic communiqué. In the 21st century, luxury is no longer just something to be worn. It is wielded.

Sanctions in Silk: When Luxury Becomes Law

The deliberate targeting of couture in sanctions regimes is more than a symbolic flourish. It reflects a recognition by lawmakers that fashion is not simply commerce but a key marker of elite legitimacy. The European Council’s 2022 Regulation 833/2014 amendment explicitly prohibited the export of luxury goods to Russia above a €300 threshold. The United States, under its International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), mirrored the measure, classifying high-end apparel alongside watches, jewellery, and vehicles.

These are not accidental inclusions. Luxury sanctions are designed to cut off the cultural lifeblood of elites — the objects through which power performs itself. For oligarchs, couture is not indulgence but armour: the gown at a gala, the suit at a summit, the accessory in a carefully staged photograph. Denying access to these items is not merely about trade; it is about rupturing the stagecraft of legitimacy.

Legally, these sanctions test the boundaries of international trade law. The World Trade Organization (WTO) ordinarily prohibits arbitrary trade restrictions, yet Article XXI of the GATT allows broad exceptions for “essential security interests.” States deploy this clause expansively, justifying bans on luxury goods as necessary for international peace and security. What emerges is a striking jurisprudence: a Paris runway dress placed in the same legal category as an arms shipment.

Couture, Courtesy, and Contraband

This dual identity of fashion — as both courtesy and contraband- is central to its diplomatic role. In peacetime, garments act as gestures of goodwill: a sari gifted at a state banquet, a bespoke suit worn in symbolic colours, a couture gown chosen to honour a host nation’s heritage. These choices soften borders, translating culture into a form of diplomacy.

In times of conflict, however, the same garments are refashioned as contraband. Under EU sanctions, a couture dress may not cross a border into Moscow; under U.S. law, a luxury handbag may be seized in transit. The absence of these objects becomes a statement in itself.

This reclassification is not merely rhetorical but legal. A gown once treated as a cultural export is redefined as a restricted commodity, its shipment scrutinised, intercepted, and penalised under customs law. The transformation underscores fashion’s volatility as an object of law: celebrated one season as heritage, criminalised the next as a sanction.

The Semiotics of Absence

To bar an oligarch from a Balenciaga suit or a Dior gown is to strip them of more than fabric — it is to strip them of narrative control. Luxury fashion is the semiotic system through which elites project belonging to a global aristocracy of taste. Without it, their image is provincialised, their prestige diminished.

This symbolic exclusion is as significant as material deprivation. Sanctioning wardrobes operate as a form of reputational exile: the elite body, once draped in Paris and Milan, is now marked by its exclusion from those circuits. A red-carpet photograph denied is a signal to the world that the sanctioned figure no longer belongs to the fraternity of privilege.

Legal scholars note that this reputational dimension is not incidental but strategic. By cutting elites off from couture, states aim not only to pressure regimes economically but to fracture the image-making machinery that sustains their authority. In other words, the law weaponises absence.

Contraband Couture: The Enforcement Paradox

Yet the legal neatness of sanctioning couture unravels in practice. Unlike oil or steel, couture defies standardised classification. Each garment is bespoke, its value a function of artistry, rarity, and brand reputation rather than quantifiable metrics. When the EU imposed its €300 threshold, customs officials faced an impossible calculus: how to price the inimitable.

The ambiguity creates fertile ground for evasion. Reports of luxury goods entering Russia through intermediaries in Turkey, the UAE, and Central Asia illustrate the porousness of enforcement. Fashion, once an emblem of legitimacy, acquires the illicit allure of contraband. Black-market couture circulates in shadow economies, stripped of its diplomatic prestige but imbued with a rebellious glamour.

This paradox underlines the challenge for regulators: in weaponising couture, law inadvertently amplifies its symbolic power. A banned Chanel suit becomes more than clothing; it becomes a political statement, worn defiantly in spaces beyond the reach of Brussels or Washington.

Fashion Houses as Reluctant Diplomats

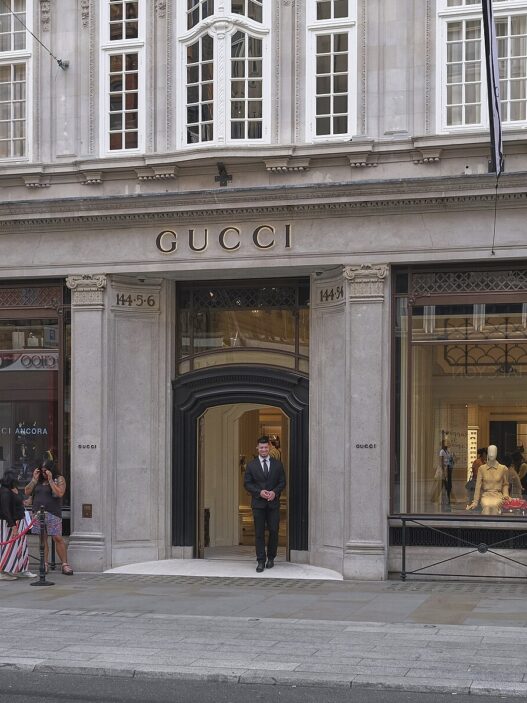

For fashion houses, compliance with sanctions is a matter of law, but also of image. Chanel, Hermès, and Louis Vuitton closed Russian boutiques in 2022, citing alignment with EU regulations. Their decisions, however, reverberated as cultural signals. Withdrawal was read not only as legal compliance but as a moral stance, reinforcing fashion’s role as a form of silent diplomacy.

Yet maisons occupy a precarious position. They are non-state actors burdened with state-like responsibilities. A misstep in compliance risks penalties; a misstep in messaging risks a reputational crisis. In effect, fashion houses act as reluctant diplomats, their boutiques transformed into stages where international law performs itself.

Fashion Under Lock and Law

Sanctioning wardrobes forces us to confront a truth too often overlooked: luxury fashion is not peripheral to geopolitics but central to its choreography. The denial of couture does not topple regimes, but it recalibrates images, punctures prestige, and isolates elites in ways that speeches cannot.

The runway and the regulation book, though distant in appearance, are intimately entangled. In today’s conflicts, garments migrate from banquets to blacklists, from gestures to sanctions. Fashion does not merely reflect politics; it enforces it.

The sanctioned wardrobe is not absent, but evidence: proof that in the 21st century, silk and statues are woven into the same cloth of power.

References

- Council Regulation (EU) No 833/2014, Concerning Restrictive Measures in View of Russia’s Actions Destabilising the Situation in Ukraine, as amended. European Parliament & Council, Official Journal of the European Union. (Especially Article 3h and Annex XVIII).

- Regulation (EU) 2022/428, amending Regulation 833/2014 (on luxury goods export restrictions) — for the updated provisions related to luxury goods.

- The WTO Analytical Index: GATT 1994, especially Article XXI (Security Exceptions). World Trade Organization.

- Van den Bossche, Peter L. H., & Sarah Akpofure. “The Use and Abuse of the National Security Exception under Article XXI(b)(iii) of the GATT 1994,” WTI Working Paper No. 03/2020.

- “Security Exception in WTO Law: Entering a New Era.” American Journal of International Law. (Discussions of how Article XXI has been invoked in recent disputes; analysis of “essential security interests”.)

- Cambridge University Press & Assessment Misra, Kartikey Vipul. “Analysing the ‘Self-Judging’ Nature of Article XXI of the GATT.” International Journal of Legal Science & Innovation Vol. 4, No. 1 (2022), pp. 593-606.

- Duong Anh Son & Tran Vang-Phu. “The Non-Discrimination Principle and the National Security Exception under GATT Article XXI: An Analysis of the Revocation of Russia’s Most-Favoured-Nation Status by the US and Its Allies.” Journal of East Asia & Int’l Law, Vol. 16, No. 1 (2023), pp. 147-158.