Fashion, since time immemorial, has been restricted to the rich and the affluent. Trends are made in the ateliers and the boutiques, while the working class waits for the trends to trickle down to department stores and corner shops. Trends have been set by the bourgeoisie and were followed by the proletariat.

However, everything changed in the 1970s when a force emerged that defies the norm, disrupts the status quo, and sends shockwaves through the fabric of society. Charged with raw energy, a defiant attitude, and a unique fashion sense, the Punk movement became a symbol of rebellion and subversion. In this article, we embark on a journey into the captivating realm of punk fashion, unraveling its origins, dissecting its key elements, delving into iconic subcultures, and uncovering its indelible influence.

The Origins of Punk

The 1970s was a time of political and social upheaval, characterized by frequent coups, government scandals, political conflicts, and tensions between different international sects due to the Cold War. Youth participation in politics increased, with young activists pioneering the anti-war, environmental, women, and LGBTQ+ rights movements. On the other hand, the 70s marked the beginning of the “Me generation” characterized by individualism, advocacy for personal liberties, and self-help.

In popular media, especially Hollywood, restrictions on violence, obscenity, and sexual content loosened. The Beatles broke up in 1970, and the public turned to other popular artists such as Queen, Rolling Stones, ABBA, and Bees Gees. But some sections of the population were becoming tired of the mainstream, constituted by disco music, Hippies from the 60s, and a few rock and roll bands. They sought a subversion from the status quo, an aesthetic that both shocks and intrigues.

This marked the origin of Punk. Punk is, in its essence, a subculture rooted in Punk Rock music and deeply held anti-establishment values. It is characterized by its extremely subversive look, DIY ethics, and a penchant for activism, rebellion, and promiscuity. But to reduce the punk movement to a bunch of rebellious kids running around does injustice not only to the movement as it was in the 70s but also discredits the impact it has to this day.

“The appeal of punk… For me…lay in its negative identity. Punk demanded total devotion, to be expressed as total rejection of everything that was not punk,” told Kelefa Sanneh in his essay The Education of a Part-Time Punk. Punk rock artists such as Sex Pistols, the Ramones, and The Velvet Underground featured provocative and politically charged lyrics in their songs and soon acquired a cult-like following.

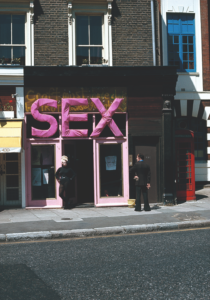

The subculture emerged around 1974 in New York and 1976 in the UK. A landmark moment in Punk fashion was the opening of Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren’s shop “Sex” in the UK. Their designs had an unshakable influence on the punk movement. McLaren also managed the Sex Pistols at that time and used them as a canvas to showcase their collections. This skyrocketed Vivienne Westwood to fame, and her contribution to the fashion world made her one of the most influential designers of the 20th century.

SEX, King’s Road SW3, 1976/1977 (Sheila Rock)

The Politics of Punk

The Punk subculture emphasizes individual freedom, with ideas of non-conformism, anti-authoritarianism, direct action, and anti-corporate narratives stitched through its music, fashion, and artistic work. Slogans, phrases, and imagery echoing the “punk philosophy” is present in punk rock songs, zines, artistic work, and even on t-shirts and outfits.

The most important aspect of Punk is its anti-consumerist ideas and the Do-It-Yourself “DIY” ethic. Since many of the members of the subculture were from lower-income groups and the working class, the members DIYed everything from clothing to music and films. Access to influential publishers, labels, and designers to fund their work was limited for most of the members. Thus, they published their own underground zines, papers, albums, and music. This strengthened the anti-consumerist philosophy of the movement, wherein members were encouraged to make do with what they had instead of funding big corporations and designers who sought to commercialize the punk aesthetic for their own gain.

1970 Punk Zines (Flickr)

Punk; The Anti-Fashion Fashion Movement

Anti-fashion refers to a deliberate rejection or subversion of mainstream or conventional fashion trends and norms. Unlike traditional fashion, which aims to dictate and perpetuate trends, anti-fashion embraces a more individualistic and unconventional approach. This can involve second-hand shopping, DIY fashion, deconstruction, and avant-garde designs.

Anti-fashion is often associated with non-conformity, self-expression, and the questioning of societal norms, similar to the way Punks viewed fashion. It can serve as a means of rebellion against the commercialization and homogenization of fashion, promoting individuality, creativity, and personal style. Discussing the process of “destroying” the clothes, Malcolm McLaren wrote, “I had succeeded in taking an article of clothing that was crisp and new and white and making it into a thing that now suggested something wild and primitive. This wasn’t fashion as a commodity. This was fashion as an idea.”

However, commodification and commercialization of the punk aesthetic soon became an issue. Malcolm McLaren, who managed the Sex Pistols and worked with Vivienne Westwood in her early years, has been criticized by many for commodifying and profiting off the punk movement. According to the New York Times, he stated in an interview, ”It is not a question of selling anything. I never did anything to sell. I designed things to upset people.”

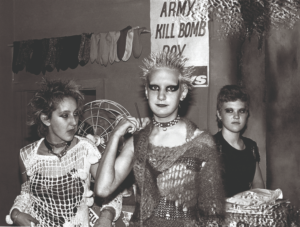

SEX PISTOLS, LONDON 1977 (JANETTE BECKMAN)

The Punk Look

The Punk look is extremely diverse, ranging from the minimalist leather jackets and torn jeans of the Ramones to the hardcore and provocative styles in the UK.

In a rejection of mass-produced conformity, punk members customized everyday clothing themselves for aesthetic effect; clothes ripped, patched up with safety pins, and distressed. Screen printing became extremely popular, and popular motifs were juxtaposed against anti-establishment slogans on t-shirts and jackets. Richard Hell, who played with bands such as Neon Boys and the Voidoids, recalled the movement in 1988, ”We wore ripped-up clothes because we wanted our insides to be outside. The whole intention was to deliver your core self without any filters.”

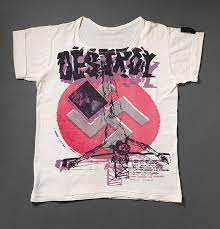

Leather, rubber, and PVC clothing were popular too, along with fetishwear for their transgressive shock value. Early punks were notorious for including sensitive symbols such as the swastika for shock value on their clothing, despite the movement openly renouncing fascists and nazis. For example, the Vivienne Westwood DESTROY shirt featured an upturned crucified Jesus and a swastika.

Body modifications, tattoos, jewelry, and spiked hairstyles on brightly colored hair were sported by punk enthusiasts, along with Dr.Marten boots, leather jackets, and tight skinny jeans. One of the most remarkable aspects of the movement is the normalization of crossdressing and androgyny. Punk men were often seen wearing skirts, fishnets, and makeup, and women were seen wearing combat boots, oversized attire, and traditionally masculine clothing. The movement challenged all conformist ideas of society, including gender dichotomy.

Interior of BOY: shop girls at work (Sheila Rock)

Controversies and Criticisms

The nature of the punk movement as a provocative and rebellious subculture makes it a hot topic of criticism–some valid, some weak. A few valid criticisms of the movement include:

- Use of swastika and other sensitive symbols for shock factor

- Encouragement and romanticization of substance and drug abuse

- Punk movement being a predominantly white-dominated subculture

- Differential Treatment of female punk musicians in studios

- Plagiarism and copyright infringements by punk brands against other fellow punk brands and mainstream designers

Vivienne Westwood DESTROY T-shirts, 1977 (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Punk Today

Punk today is a watered-down version of what it was in its heyday. Intense commercialization and appropriation of the punk aesthetic by bigger designers and corporations have erased the DIY, rebellious ethos of the original subculture and integrated it into the mainstream.

The high-fashion and mainstream market remakes of punk fashion are underwhelming and performative. Dick Hebdige, in his book Subculture, explains this perfectly:

“Once removed from their private contexts by the small entrepreneurs and big fashion interests that produce them on a mass scale, they become codified, made comprehensible, and rendered at once public property and profitable merchandise.”

This signifies the death of punk, for the main appeal of punk was its subversion from the mainstream. The appropriation of punk culture by the upper echelon results in a marketable yet weak imitation of the original aesthetic. A few examples of this include the Paco Rabanne SS23 show and Oscar De La Renta Fall 2020 collection.

Appropriation is an inevitable phenomenon in fashion. Inspiration is taken and given, and ideas and creativity constantly flow across high and low fashion. But the roots of the inspiration shall be acknowledged, however “unglamorous” it may be. Perhaps the best way to truly appreciate the punk ethos is through tearing a t-shirt yourself, not cashing out to let a designer tear it for you.

References:

Valerie Steele (1997) Anti-Fashion: The 1970s, Fashion Theory, 1:3, 279-295, DOI: 10.2752/136270497779640134

Art Collection. (1 C.E., January 1). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection

Hebdige. (1979). Subculture: The Meaning of Style.

Capelle. (2023, March 1). The working class aesthetic is cool now? [Video]. Youtube. Retrieved June 22, 2023, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8hnnQrL57hM&t=624s&ab_channel=AliceCappelle

Hochswender. (1988, September 27). Patterns; Punk Fashion Revisited. Https://Www.Nytimes.Com/. Retrieved June 22, 2023, from https://www.nytimes.com/1988/09/27/style/patterns-punk-fashion-revisited.html

McLaren. (1997, September 14). Elements of Anti-Style. Newyorker.Com. Retrieved June 22, 2023, from https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1997/09/22/elements-of-anti-style

Sanneh. (2021, September 6). The Education of a Part-Time Punk. Newyorker.Com. Retrieved June 22, 2023, from https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/09/13/the-education-of-a-part-time-punk

Beer, D. (2014, January 6). Punk Sociology. Palgrave Pivot.

By Srinidhi Madurai K, Intern at FLJ