When the Africa Cup of Nations (AFCON) takes centre stage, as it unfolds from December 2025 to January 2026, the spectacle isn’t confined to goals and trophies. Across stadiums in Morocco and on social feeds globally, the tournament also showcases an evolving fashion narrative. The kits worn by players (bold, expressive, and rich with cultural motifs) have become more than uniforms. They are cultural signifiers, commercial assets, and increasingly legal subjects. But amid identity, pride, and design, a crucial question emerges: who really owns the story behind these jerseys?

At AFCON 2025, kits from Nigeria, Morocco, Senegal, Mali, Cameroon and others drew attention for more than performance. Senegal’s vibrant patterns, Nigeria’s brushstroke motifs, and Morocco’s geometric references all became part of the tournament’s visual identity. Fans now wear these jerseys with pride, and designers regularly push their creative boundaries. Yet behind that enthusiasm lies a legal reality that’s far from straightforward.

Official Kits and the Chain of Rights

At the core of every national team kit is a contractual relationship between a football federation and a supplier. Unlike club football, where global brands dominate, AFCON 2025 showcased notable brand diversity: seventeen different kit makers outfitted the tournament, with Puma leading the pack and traditional giants like Nike and Adidas appearing less often than expected.

These agreements typically grant the supplier rights to manufacture, distribute, and market jerseys bearing national colours, crests, and associated IP. The football federation generally owns the trademarks and symbols (often registered locally and internationally) and licenses them to the kit maker in exchange for royalties or fixed fees.

In practice, this creates a layered intellectual property ecosystem:

- Federations control team identity: emblem, colours, and official marks.

- Equipment brands own kit designs and related technologies.

- Licensees and retailers generate revenue by selling replicas to fans.

Trademark and industrial design law form the legal backbone of this ecosystem. By registering and enforcing their marks, federations maintain control over team symbols and colours and can prevent unauthorized commercial use. In practice, this is their main defence against infringers. Yet, the level of protection varies significantly from one country to another, depending on registration habits, institutional capacity, and political will.

Cultural Arrival: When Tradition Leads the Way

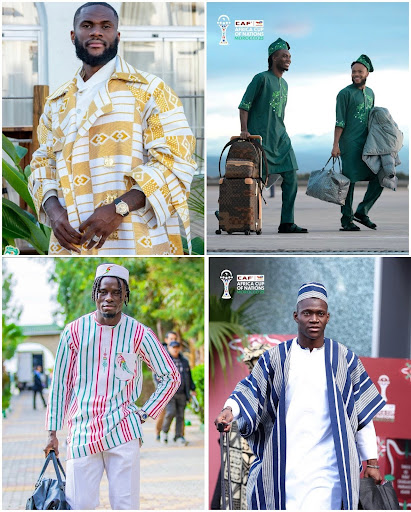

Before a single match was played in Morocco, AFCON 2025 delivered an unexpected cultural moment in airport arrival halls. Teams exited planes wearing traditional attire that highlighted the textile heritage of their respective countries. Mali’s bogolan, Burkina Faso’s faso dan fani, Cameroon’s nkanda tunics, or the jellabas of North Africa all appeared, each carrying meaning beyond aesthetics. This unofficial “arrival runway” became a showcase of national identity and regional pride.

These outfits sparked discussion not about branding, but about belonging. Unlike matchday kits shaped by licensing deals and IP, traditional garments aren’t designed for commercial reproduction. They are cultural expressions, worn with dignity and not intended for sale. Legally, they generally fall outside IP protection unless they are transformed into distinctive, registrable fashion designs or brand identifiers.

Their visibility at AFCON underscores a limit within IP law: collective heritage sits awkwardly in systems that favour individual ownership. These fabrics and patterns are shared, living, and transmitted across generations. In a tournament increasingly shaped by commercial rights, the players’ choice to arrive in unbranded attire felt refreshing..Beyond the Official Field: Streetwear, Local Brands & Identity

Official kits represent only one chapter of AFCON’s fashion story. Across the continent, fashion entrepreneurs have built independent lines inspired by football culture. Brands such as ASHLUXE, Daomey Store, and High Fashion reinterpret national colours and motifs into streetwear tied to football heritage.

These brands operate outside federation contracts, drawing on inspiration rather than licensed use. Legally, that difference matters. As long as they avoid using protected marks, crests, or confusingly similar symbols, they typically stay clear of infringement. This space shows how cultural expression and IP can coexist, allowing creative communities to participate in the aesthetic ecosystem without stepping on exclusive rights.

The Reality of Counterfeits in Informal Markets

Alongside official and independent fashion lies a long-standing reality: counterfeit sportswear. In markets from Abidjan to Dakar, unofficial jerseys using national colours are sold at accessible prices. These products mimic official looks but bypass trademark rights that federations and brands have invested in.

Counterfeits raise both legal and social questions. Legally, they infringe trademark and design rights when they reproduce protected symbols. Socially, they reflect purchasing power dynamics: official replicas can be expensive, and demand for affordable alternatives remains high.

Several African jurisdictions have anti-counterfeiting laws that allow civil or criminal enforcement. South Africa’s Counterfeit Goods Act is one example. Yet enforcement depends on coordinated customs, policing, and political accountability, and remains uneven in practice.

When IP Meets Identity: Challenges and Opportunities Ahead

AFCON lives at a crossroads where fashion, culture, and law constantly interact. Official kits operate as commercial products backed by IP rights. Independent designers contribute their own interpretations, sometimes pushing the culture in new directions. Informal markets and counterfeits still circulate, making ownership and access more complex than federations would like.

For legal teams advising federations or fashion houses, the priority is to reinforce trademarks and designs, secure licensing deals, and think ahead about enforcement. At the policy level, it may also be time to explore how IP frameworks can acknowledge cultural heritage without weakening formal protection systems. The goal is simple: that jerseys serve not only as symbols of pride during the tournament, but as protected and meaningful expressions of identity throughout the year.

References

- Collage 1 : The Best Kits of the 2025 Africa Cup of Nations – nss sports

- Collage 2 : Players from : CIV, Nigeria, Burkina Faso, Mali wearing traditional attire – @CAF_Online, Instagram

- The Best Jerseys from AFCON 2025: The Kits That Defined the Tournament’s Aesthetic,” NSS Sports, Jan 9 2026.

- All Africa Cup of Nations 2025 Kits – Adidas & Nike Have One Team Each Only, Footy Headlines, Dec 19, 2025.

- PUMA Reveal AFCON 2025 Kits for Egypt, Côte d’Ivoire, Morocco, Senegal & Ghana, SoccerBible, Nov 15, 2024.

- Official AFCON Store – CAF Store (jerseys), CAF online.

- Africa – An Ideal Market for Brand Holders and Counterfeiters, Kisch IP.

- Counterfeiting in Africa: An A‑Z Guide, Spoor & Fisher.

- Jellaba, Bogolan, nkando, faso dan fani: le défilé des identités …

- L’Afrique en couleurs : les équipes de la CAN 2025 posent le pied …