Indian Classical Dance: An Interpretation

Classical dance in India is not just dance; it is a whole other world. You walk into a show and suddenly there’s silk everywhere, jewellery catching the light like it’s showing off, ankle bells doing their own heartbeat thing, and you just feel it; this sacred, almost untouchable vibe.

And then, ugh, you see bits of it spilling out where it doesn’t belong. On the street. On fashion ramps. In random Instagram reels. Hanging in shop windows like it’s just another accessory. And I’m sitting here thinking: this isn’t me being dramatic, okay? This is me as a dancer going, “hey, this hurts,” and as a lawyer going, “yep, I know exactly why this is a problem.”

Why do classical dance forms need to be protected?

Every classical dance form in India is steeped in centuries of rich meaning. The costumes? They’re not just random, pretty fabric; they’re stories you can literally wear. Stories about gods, philosophies, rituals, and the places they come from. Same with the jewellery: the nath, the maang-tikka, the waistband, they are not just “cute accessories.” They are identity. They are devoted. They are a tradition.

But now? These powerful visuals are everywhere: fashion ramps, wedding décor, and ad campaigns. Half the time, they are yanked out with no context, no credit, and nothing. Just aesthetics stripped from their roots.

It’s like turning a sacred temple bell into a nightclub prop; flashy, yes, but stripped of meaning.

Here’s the messy part — most of these visuals do not actually have strong legal protection. No solid fences around them. If they are not registered as designs or tagged with a geographical indication, it’s open season; anyone can copy, tweak, remix, and sell them without a second thought. Something that took five centuries to grow, perfect, and pass down can be reduced to an “ethnic edit” in just one weekend photoshoot.

Let’s get one thing straight — appreciation is not the same as appropriation. Wearing the style of a classical dance costume without knowing the meaning behind it isn’t “creativity.” And using it in some tacky ad or a Bollywood item number? That’s not innovation, that’s dilution. Every time it happens, a little bit of the art form’s soul gets chipped away, along with the legacy of the people who have kept it alive for centuries.

Preserving and Protecting Fashion in Classical Dances

India has eight primary classical dance forms, but in this article, I will be discussing five of them: Kathak, Bharatanatyam, Kathakali, Odissi, and Manipuri. I want to draw a line between how we preserve fashion in these traditions and how we protect our intangible heritage as a whole. And yes, we’re going to get into the legal side of it too. Because those costumes, those aesthetics, those little details; they deserve protection, not just praise.

You know, in the pleats of a Bharatanatyam sari, the spin of a Kathak lehenga, or the vast, fierce mask of Kathakali: there’s more than just art. There’s history and identity. These dances are not just for show. They hold language, philosophy, devotion, all packed into movement and costume. But here’s the problem: the world’s moving fast, chasing trends, selling culture like it’s just another product. And when that happens, these traditions get watered down, twisted, sometimes even stolen.

That’s when the law has to step in. Not as some boring rulebook, but as the guard at the door, making sure the grace and dignity of these art forms don’t get trampled.

How does law come into the picture?

Intellectual Property Rights are one of the biggest shields we have for protecting classical dance traditions. The Copyright Act, 1957, actually covers a lot more than people think. Section 13(a) says original literary, dramatic, musical, and artistic works are protected. And yes, that includes choreography and costume designs. Section 2(h) even spells it out: choreographic works count as dramatic works, which means the choreographer owns them.

Section 17 makes it clear — the original creator is the first copyright owner, unless the work was done on commission or as part of a job. If someone uses, copies, or twists that work without permission, Section 63 is there to treat it as an offence. There’s also a moral rights clause that lets artists stop others from misrepresenting their work — not many people know that. And it doesn’t stop at dance steps. Sections 2(c) and 2(ff) also protect costume sketches, embroidery designs, and even the audio recordings of performances.

Beyond copyright, trademarks are a big deal when it comes to protecting the identity of classical dance: the schools, the gurus, even the unique look that comes with each tradition. Under Class 41 of the Trade Marks Act, 1999, any goods or services related to education, training, entertainment, or cultural activities can be registered. So, yes, your dance academy’s name, the title of your annual show, or even a production brand can be legally protected, ensuring nobody else can use it.

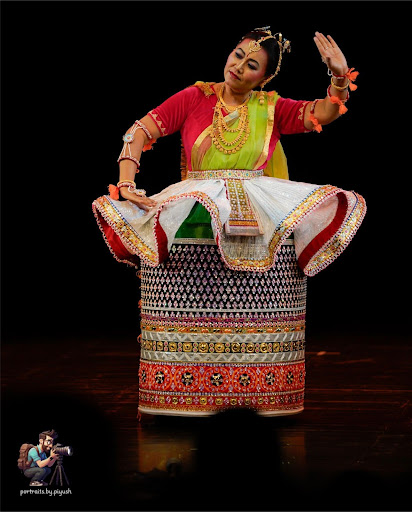

Then there’s Class 25, which covers clothing, footwear, and headgear — and that’s where it gets interesting. Because in classical dance, costumes aren’t “just clothes.” They’re signatures of tradition. The Taihya in Odissi — that floral or beaded crown-like headpiece. The Chandrasuryan jewellery in Bharatanatyam symbolises the sun and moon. The elaborate Kumil in Manipuri — that stiff, barrel-shaped skirt glowing with gold and silver embroidery. All of these can be trademarked to prevent them from being copied, misused, or diluted.

Section 29 of the Act is what deals with infringement: basically, if someone uses your registered trademark or something that looks just like it without your permission, and it causes confusion, they’re in the wrong. For dancers, that means the name of your guru, your school’s logo, or the distinct visual identity of your production can be officially protected. It’s about keeping your brand – and your lineage — safe from people trying to ride on your name.

And it doesn’t stop there. The Geographical Indications of Goods Act, 1999, adds another layer of protection. A GI tag basically says, “This thing comes from here and here alone.” For dance, that could mean fabrics, jewellery, costume designs, even types of ghungroo that are unique to specific regions. It’s about making sure that when something claims to be from a tradition, it truly is; not just a copy dressed up for commercial use.

Take ghoongroos, for example. In Bharatanatyam, they are neat, symmetrical, and usually have about 50–100 bells on each foot. The sound is soft and melodic — perfect for the grounded, devotional nature of the dance. Kathak ghoongroos? Completely different vibe. They’re tied in thicker layers, sometimes with 100–200 bells, and the sound is sharper, more resonant — precisely what you need to make those lightning-fast footwork patterns and chakkars stand out. These aren’t just bits of metal on a string — they are products of regional craftsmanship and performance philosophy. That’s why they’re perfect for GI protection.

Costumes in classical dance are more than just clothes; they come straight from the culture and region they belong to. Take Bharatanatyam, for instance. The costume is inspired by the traditional attire of a Tamil Hindu bride. Usually, it’s a bright silk sari, stitched to make a fan-like pleat that spreads beautifully when the dancer moves. And then there’s the jewellery—waist, neck, ears, nose, head—everything that finishes the look.

Kathak is entirely different. It has both Hindu and Mughal influences. In the Hindu style, dancers wear a flared lehenga with a fitted choli and a dupatta. The Mughal-style Kathak features a churidar, a long kurta or angarkha, an orhni or scarf, and sometimes even an overcoat that covers the arms and head. Every outfit tells a story, not just in its appearance, but in how it moves with the dance.

Then there’s Kathakali, from Kerala. This one’s a whole performance in itself. Getting into costume takes hours: layers of colourful skirts, huge headpieces, and painted faces. Every single colour, every detail, has meaning. The costume isn’t just decoration; it is part of the story. The noble green face of pachcha brings to life virtuous heroes like Krishna and Rama, while the fiery red of tati marks fierce villains such as Ravana. Black is the shade of hunters and forest-dwelling demons; yellow graces sages and noble women, such as Sita; and the rare white-bearded look embodies purity and devotion, most famously in Hanuman. Alongside the makeup, handcrafted masks and ornaments — shaped by generations of Kerala’s artisans — hold a heritage of their own, making them worthy of protection under the Geographical Indication (GI) tag.

The Act doesn’t just give protection — it also stops people from misusing it. Section 21 basically says that if you’re not authorised, you can’t use a registered GI in a way that tricks people or cashes in on its reputation. In classical dance, that means you can’t just take the name of a gharana, copy a particular costume style, or claim a region’s signature design as your own without the right to do so or without giving proper credit. Using the GI Act in this way means these parts of our culture get appropriate legal protection.

International Provisions for Preserving Traditions

In September 2005, India signed UNESCO’s 2003 Convention on safeguarding intangible cultural heritage. In plain terms, it was a way of saying—we value our traditions and we’re willing to take steps to protect them. The Convention, in Article 2, discusses topics such as Performing Arts and Traditional Craftsmanship. That’s precisely where our classical dance forms fit in, along with the jewellery, costumes, and the little artistic touches that belong to them.

Article 11 says it’s the State’s job to step in—through laws, systems, or even funding, so that these traditions aren’t lost. But there’s another side to it. Article 15 reminds us that it’s also about the people, communities, groups, and even individuals taking an active role. In the case of dance, that could be gurus writing things down, schools preserving old designs, or local artists keeping the craft of ghoongroo-making alive. The government? It should be the hand that supports all of this, not the one that takes it over.

Conclusion

Keeping these classical traditions alive isn’t just about laws; it’s about preserving the essence of these traditions. The communities that live and breathe them carry most of the responsibility. Rules can set the stage, but it’s really people paying attention, showing respect, and actually recording and passing things on that keep these traditions alive. That’s how they survive—not just in papers or official documents, but in the everyday practice and care of those who love them.

good work sharvi , keep it up

Indeed a great effort to save our culture and heritage. Congratulations and wish you good luck for upcoming columns.

Very good sharvi, great thought n initiative

All the very best

very well written

She has captured the heart of preserving cultural heritage – it’s not just about rules and laws, but about the passion, respect, and dedication of the communities who live and breathe these traditions. Every line highlights the importance of intergenerational transmission and the role of individuals in keeping these traditions vibrant and alive.

Well done Sharvi 👍

each dance form encapsulates the essence of India’s cultural heritage, captivating audiences with its elegance and timeless beauty. Well done Sharvi.❤️

Very insightful article and an honest attempt to save and potray the culture and story behind the outfits which give meaning to the traditional indian classical dance forms.

Very insightful and very well written, great work sharvi ji

“Truly inspiring read—your article sheds light on such an important subject with great clarity. Congratulations on this meaningful contribution!”

This is a beautifully written article with rich insights. I really appreciated how you highlighted the role of dance and traditional dress in preserving cultural heritage – it brings history alive in such a creative and engaging way. The storytelling is thoughtful, and it gave a deeper understanding of why these traditions are worth cherishing. Overall, a very impactful piece that leaves the reader both informed and inspired.

What an insightful and interesting read ! Truly a great effort to preserve and transmit our cultural inheritance to young generations.

Looking forward to have such more interesting and insightful articles.

अति सुंदर very well written and also very meaningful keep it up प्रभु श्री हरि का आशीष सदैव आप पर ऐसा ही बना रहे

Awesome Sharvi👌

In the era of ” phoohad ” drama in the music / dance,you people are the little but brighter flame in saving our traditional classical music and dance culture. Keep it up👍

Wonderful Topic and Heading, though law preserve & safeguard Rights of All nationals but this thought is out of the box thinking, Keep it up Sharvi & other team members.

अपनी सांस्कृतिक विरासत को सामाजिक, बौद्धिक और क़ानूनी तरीकों से समझने, समझाने और बचाने का एक बहुत अच्छा प्रयास है शाबाश।

Thank you Sharvi for such a brilliant article on awakening the people to protect their heritage by themselves not dropping everything on the hands of govt or law. Also encouraging people to know there culture because appreciation is not the same as appropriation.

An excellent effort in keeping our art and heritage alive. This article is a combination of literary awareness and cultural exuberance of our country.

A lot of patience and perseverance is required to achieve the desired goals. And I know that you possess it. Keep it up. Our blessings are always with you. GOD bless you! 🙏🙏🌹❤️

You really are doing tremendous service to keep alive the most ancient dance form of Hindustan, well done best wishes, hope more articles like this one shall follow.

one can sense with the quality of the writing that u have talked about something that truly matters to you and what actually deserves attention too. very well written sharvi, many more publications to come!!

Congratulations, Sharvie! Such a proud moment to see your article published in the Fashion Law Journal. Loved the way you connected heritage & law.