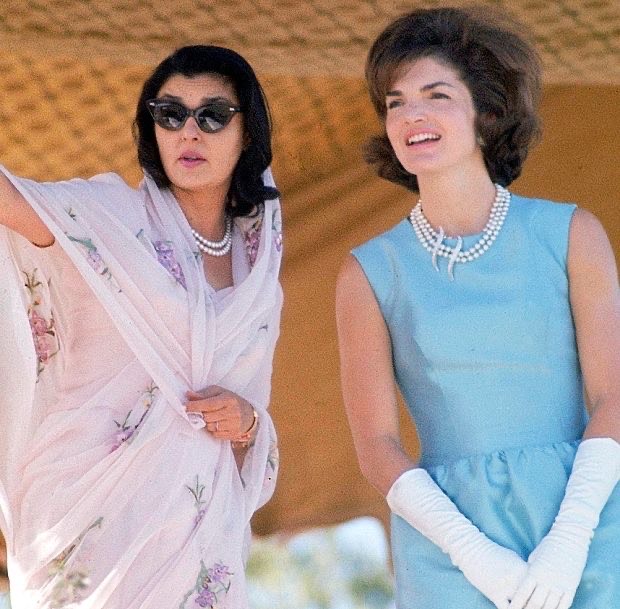

In the honeyed afternoons of Jaipur, where the air hums with the scent of marigolds and history lingers in the sandstone corridors of City Palace she still walks- if not in presence, then in legend. Maharani Gayatri Devi, the last queen of an era where elegance was effortless and regality was not learned but inherited, remains immortal. The rustle of her chiffon saris, softer than the whisper of the desert wind, and the glint of her unadorned pearls, understated yet commanding, are stitched into the very fabric of Indian luxury. She was a woman who turned heads but never needed to. A princess born into opulence, a queen who defied expectations, a parliamentarian draped in pastels- her contradictions only made her more compelling. Even decades after her time, her name evokes the kind of aristocratic glamour that designers still chase, that brands still borrow, that cultural nostalgia still clings to. She has been reborn in mood boards, in fashion collections, in the delicate folds of chiffon that designers drape in her name, in the curated nostalgia of a past that still shimmers like gold- dusted embroidery.

But in an era where nostalgia is not merely remembered but repackaged, where heritage is not just revered but relentlessly replicated, the ‘Maharani Aesthetic’ has become both muse and commodity. Once a symbol of effortless aristocracy, it now flutters through the ateliers of luxury houses and the production lines of fast fashion alike- some in homage, others in quiet transgression. The pastels, the pearl strung elegance, the gossamer-light chiffons once woven into royal legacy are now stitched in commerce, duplicated without provenance, borrowed without attribution. The question that lingers, much like the scent of marigolds in the “Jeypore” air, is this: Can an aesthetic so deeply enshrined in history be safeguarded from dilution? Can the intangible essence of royalty be legally preserved, or does inspiration, once set free, belong to all who dare to claim it?”

The whisper of chiffon, the structured yet effortless drape of a sari, the interplay of pearls against the pastel silks- Maharani Gayatri Devi’s signature style was never a mere ensemble; it was a language of understated affluence. Yet today, that language is being spoken without provenance. From the artisan-laden ateliers of Sabyasachi to the mass market machinery of Zara, the allure of ‘royal fashion’ is no longer privy to those born into palaces. It is a global commodity, but one that begs legal reckoning: when does cultural homage become fashion plagiarism?

The Legal Stitch

Unlike a logo (protected under trademark law) or a specific garment design (safeguarded by The Designs Act, 2000 in India), an aesthetic is far more elusive. The Maharani Aesthetic is not a singular creation but a collection of stylistic signatures—the airy pastels, the translucent chiffons, the restrained grandeur of uncut diamonds. Fashion law does not easily shield such intangibles from replication.

Yet, luxury houses have long battled over proprietary aesthetics. Chanel has fought legal wars over its quilting patterns, Burberry has waged trademark disputes over its signature check, and Louboutin has defended the very colour of its soles in courtrooms across the world. Could a similar argument be made for the visual lexicon of Indian royalty? Could the heritage of a queen be grounds for legal exclusivity?

Heritage in Fast Fashion: A Lost Legacy?

In the glaring fluorescence of fast fashion showrooms, heritage is stripped of its depth and repackaged in synthetic blends and machine-cut embroidery. A once-luxurious silhouette finds itself flattened into polyester, its grandeur reduced to a SKU number. Brands like Zara, ASOS, and even high-street Indian labels have churned out Maharani-inspired designs—chiffon saris in mass production, pearl-encrusted tunics mimicking royal couture, and brocade blouses with none of the finesse of hand-woven craftsmanship.

The law, however, remains selective in its defence. While fast fashion houses have been taken to court for replicating specific patterns or embroidery styles, they remain largely untouchable when borrowing from themes rather than concrete designs. Hermès may have trademarked its Birkin, but can royalty ever trademark an aesthetic?

The Counterfeit Conundrum

Beyond the realm of fast fashion lies its shadowy twin: the counterfeit industry. In the bustling markets of Chandni Chowk, Bangkok’s Patpong Night Market, and the famed counterfeit districts of Guangzhou, the Maharani Look is no longer an aspiration—it is a cheaply manufactured reality.

Here, hand-woven chiffons are replaced with nylon blends, and ‘Jaipur Royal Collection’ tags appear on garments that have never seen the walls of a palace. The counterfeit trade, which contributes to nearly USD 500 billion in global losses annually, thrives on the absence of enforceable fashion copyrights. While Indian law offers protection under The Copyright Act, 1957 for original textile designs and embroidery, the vast expanse of ‘heritage fashion’ remains an unguarded frontier.

The implications are profound: not only does counterfeiting erode the value of luxury craftsmanship, but it also threatens the very artisans whose skill once defined these royal wardrobes. In this legal vacuum, a question lingers—can a fashion aesthetic born from nobility be safeguarded against dilution, or is its fate to be forever replicated, never protected?

The Gilded Dilemma

Heritage is an asset. In fashion, it is intellectual property with an identity, a provenance, a prestige. Yet, when aesthetics born from aristocracy are diluted into mass-market renditions, the law stands at an impasse.

For decades, the legal framework has granted fashion limited safeguards—trademarks for logos, patents for innovations, copyrights for surface designs. The intangible, however, remains unguarded. The Maharani Aesthetic—pastel chiffons, uncut diamonds, structured drapes—exists in a space between cultural homage and commercial replication. What belongs to history often becomes public domain, yet the business of fashion thrives on exclusivity. The question is no longer whether an aesthetic can be replicated; it is whether it can be legally fortified.

Legality and Legacy

Luxury houses have long crystallized their identity through trademarks, converting visual signatures into proprietary assets. In the West, the Chanel quilting, the Burberry check, the Hermes Birkin silhouette are all trademark-protected. In India, handloom weaves, embroidery techniques, and even temple jewelry designs have sought similar status.

A precedent exists: the Banarasi sari, the Chanderi weave, the Pochampally Ikat—each protected under geographical indication (GI) status. Theoretically, the ‘Maharani Look’ could be distilled into a legally recognized heritage trademark, a seal of authenticity for designs that trace their lineage to Jaipur’s royal ateliers. A legal identity that separates inspiration from appropriation, homage from hijack.

Geographical Indications: The Safeguard of Provenance

The Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act, 1999 has preserved India’s artisanal economy, offering legal exclusivity to craft-based communities. A garment labeled as Chikankari must originate from Lucknow; a Kanjeevaram silk must be woven in Tamil Nadu. If traditional craftsmanship is protected, could the aesthetics of royal wardrobes follow suit?

There is precedent. France protects its champagne, Italy its Parmigiano Reggiano. If provenance is law, then Jaipur’s couture heritage—its intricate gota patti, its diaphanous chiffon drapes, its jadau settings—could fall under similar protection. An elevated safeguard for designs that have long been a part of history, but not of imitation.

Art or Imitation

The counterfeit market has become a billion-dollar empire, replicating not just brands but legacies. In the lanes of imitation, the Maharani Look has been reduced to its synthetic knockoffs—machine-stitched chiffons, mass-produced faux pearls, brocade stripped of its craftsmanship.

Under The Copyright Act, 1957, original textile designs are protected for ten years, extendable to fifteen. Yet, the fine print is limiting. Designs that enter mass production lose copyright protection, leaving high fashion vulnerable. While the Designs Act, 2000 safeguards surface patterns and embroidery techniques, it is inadequate for the vastness of a cultural aesthetic.

Luxury houses have responded with aggressive legal enforcement. In 2022, Chanel won a counterfeit lawsuit against a network selling imitation handbags. In India, Sabyasachi and Manish Malhotra have cracked down on unauthorized replicas of their bridal couture. Yet, the law remains reactive, not preventive. A Maharani Code of Authenticity—a legally recognized certification for heritage fashion—could change the landscape, offering both prestige and protection.

Woven in Law, Draped in Legacy

The bridge between legacy and legality is yet to be built. The fashion industry has historically drawn from the past, but in an era where aesthetics become intellectual property, a framework for protection must evolve. The future of heritage fashion law will be written not just in archives but in courtrooms, defining where cultural history ends and commercial ownership begins.

But laws, like couture, can only tailor so much. The fine print of the Copyright Act and the Designs Act may seek to delineate ownership, yet they cannot entirely safeguard an aesthetic—an aura—that was never meant to be confined to legal clauses. Maharani Gayatri Devi’s legacy, much like the delicate chiffons she championed, is weightless yet enduring, slipping through the rigidity of statutes into the realm of cultural permanence. And so, the question extends beyond legal protection to something far more nuanced: Can elegance itself be copyrighted?

The Maharani, the Muse and the Mirage

Jaipur, with its rose-tinted palaces and gilded archways, remains a city where history is not merely preserved but perfumed into the air—stitched into the folds of time like the pleats of a perfectly draped chiffon sari. And Maharani Gayatri Devi, much like the city she called home, exists beyond the constraints of time, endlessly revisited and reimagined. Her legacy is not just a relic of the past but a blueprint for elegance that designers continue to borrow and brands endlessly resurrect. In many ways, she was Jaipur’s answer to Princess Diana—both women bound by royalty but unconfined by it, both style icons whose effortless grace became a language of its own, and both eternal muses, not just for fashion but for a way of being.

Yet, as fashion houses weave nostalgia into commercial allure, the question lingers—where does homage end and exploitation begin? If fast fashion can dilute the essence of a style once synonymous with exclusivity, then the law must stand as its final custodian, ensuring that history is not merely replicated but rightfully revered. For true elegance is not just what is worn but what is preserved. And in the grand tapestry of luxury, Maharani Gayatri Devi remains more than a silhouette; she is the gold thread that refuses to fade.

References:

- Vogue India, How Maharani Gayatri Devi of Jaipur Ushered in the Classic Chiffon Sari Trend, VOGUE INDIA, https://www.vogue.in/content/how-maharani-gayatri-devi-of-jaipur-ushered-in-the-classic-chiffon-sari-trend.

- Elle Canada, Chanel’s Quilted Secrets, ELLE CANADA, https://www.ellecanada.com/fashion/chanel-s-quilted-secrets.

- Christian Louboutin, Red Sole, CHRISTIAN LOUBOUTIN, https://us.christianlouboutin.com/us_en/red-sole.

- Burberry, The Burberry Check, BURBERRY, https://in.burberry.com/the-burberry-check/.

- Columbia Journal of Law & the Arts, Protecting Fashion and Cultural Expressions, COLUM. J.L. & ARTS, https://journals.library.columbia.edu/index.php/lawandarts/announcement/view/621.

- Hindustan Times, It’s a Rip-Off, HINDUSTAN TIMES, https://www.hindustantimes.com/chandigarh/it-s-a-rip-off/story-cfSQmA337gUK36jQBsblBI.html.

- World Trademark Review, Protecting Fashion and Cultural Expressions, WORLD TRADEMARK REV., https://www.worldtrademarkreview.com/article/protecting-fashion-and-cultural-expressions.

Author: Aastha Kastiya